From The New York Times: “In Texas, voters must show a photo ID. A state handgun license qualifies, but a state university identification card does not.”

Presenting the 17th Annual New England Muzzle Awards

U.S. Sen. Ed Markey, Rhode Island Gov. Lincoln Chafee, Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick and U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz (again) might consider running the other way when we try to present them with our coveted statuettes for dishonoring the First Amendment.

The 17th Annual New England Muzzle Awards are now online at WGBHNews.org and The Providence Phoenix. They should be up soon at The Portland Phoenix as well. This is the second year that WGBH has served as home base following 15 years at the late, great Boston Phoenix.

As always, the Muzzles are accompanied by an article on Campus Muzzles by my friend and sometime collaborator Harvey Silverglate. There are a couple of new touches this year as well: the WGBH design is responsive, which means it looks just as great on your tablet or phone as it does on your laptop; and WGBH reporter Adam Reilly, WGBHNews.org editor Peter Kadzis and I talk about the Muzzles on “The Scrum” podcast, which of course you should subscribe to immediately.

Peter, by the way, is a former editor of the Phoenix newspapers, and has now edited all 17 editions of the Muzzles.

Finally, great work by WGBH Web producers Abbie Ruzicka and Brendan Lynch, who hung in through technical glitches and my whining to make this year’s edition look fantastic.

Talking about Facebook and emotional manipulation

Jon Keller of WBZ-TV (Channel 4) and I talked Monday about Facebook’s experiment in surreptitiously changing the emotional content in the newsfeed of some of its users to see if it made them happy or sad.

Author and Microsoft Jaron Larnier weighs in on The New York Times’ opinion pages today, writing:

The manipulation of emotion is no small thing. An estimated 60 percent of suicides are preceded by a mood disorder. Even mild depression has been shown to increase the risk of heart failure by 5 percent; moderate to severe depression increases it by 40 percent.

And if you want to get up to speed quickly, Mathew Ingram of GigaOm has written a terrific all-known-facts round-up.

This is an important issue, and it should not sink beneath a morass of outrage about other issues — although, sadly, it probably will.

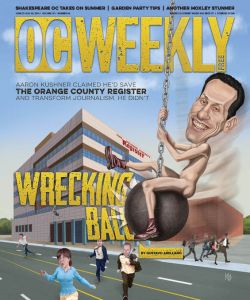

Tales of two newspapers, one rising, one falling

On the East Coast, The Washington Post is in the midst of a revival that could return the storied newspaper to its former status as a serious competitor to The New York Times for national and international news. On the West Coast, the Orange County Register is rapidly sinking into the pit from which it had only recently crawled.

On the East Coast, The Washington Post is in the midst of a revival that could return the storied newspaper to its former status as a serious competitor to The New York Times for national and international news. On the West Coast, the Orange County Register is rapidly sinking into the pit from which it had only recently crawled.

The two contrasting stories are told by the Columbia Journalism Review’s Michael Meyer, who writes about the Post in the early months of the Jeff Bezos era, and Gustavo Arellano of OC Weekly, who’s been all over Aaron Kushner since his arrival as the Register’s principal owner in 2012.

First the Post, which has been the subject of considerable fascination since Amazon founder Bezos announced last August (just a few days after John Henry said he would buy The Boston Globe) that he would purchase the paper from the Graham family for $250 million.

Bezos’ vision, as best as Meyer could discern (Bezos, as is his wont, did not give him an interview), is to leave the journalists alone and work on ways to expand the Post’s digital audience across a variety of platforms. Meyer describes a meeting that Bezos held in Seattle with executive editor Marty Baron and other top managers:

Baron says he came away from the weekend in Seattle with a clear sense of what the Post’s mission would be in the coming year: It had to have “a more expansive national vision” in order to achieve the ultimate goal of substantially growing its digital audience. Baron brought this directive back to the newsroom, and the editors set about building a plan for 2014, a year managing editor Kevin Merida dubbed “the year of ambition.” At one point in the budgeting process, Bezos even admonished the leadership for not thinking big enough. “I think that we had been in the mode of sort of watching our pennies,” Baron told me. “We were just being more cautious at the beginning so he came back with an indication that we should be more ambitious.”

Among the more perplexing moves (to me at least) that the Post has made under Bezos has been to cut deals with more than 100 daily papers across the country so that paid subscribers to those papers would receive free digital access to the Post as well. Locally, the papers include the Portland Press Herald as well as Digital First Media’s papers, such as The Sun of Lowell, The Berkshire Eagle and the New Haven Register.

Journalistically, it’s a good deal for subscribers, since they get free access to a high-quality national news source. But no money changes hands. So how is it any better for the Post than simply offering a free advertiser-supported website, as it did until instituting a metered paywall last year? Meyer tells me by email that “the reason they are doing this is for customer data. A logged in, regular user is a lot more data rich than someone who just happens across your site from time to time.” He adds:

Data is the key difference between this program and just having a free website. And another key difference to my mind is psychological. The readers of partner newspapers feel like they’re being given something that would otherwise not be free. This adds value in terms of how they view their subscriptions to their home newspapers. And also adds value in terms of how they view the Post’s content. My guess is they will use the service more as a result.

And as Meyer writes in his story, “Anyone interested in seeing how consumer data might be used in the hands of Jeff Bezos can go to Amazon.com and watch the company’s algorithms try to predict their desires.”

The story Gustavo Arellano tells about Aaron Kushner and the Orange County Register has become well-known in recent weeks, in large measure because of Arellano’s own coverage in the OC Weekly. Kushner has spent 2014 rapidly dismantling what he spent 2012 and 2013 building up.

The story Gustavo Arellano tells about Aaron Kushner and the Orange County Register has become well-known in recent weeks, in large measure because of Arellano’s own coverage in the OC Weekly. Kushner has spent 2014 rapidly dismantling what he spent 2012 and 2013 building up.

As I wrote recently in The Huffington Post, it makes no sense to invest in growth unless you have enough money to wait and see how it plays out, which is clearly the case with Bezos at the Post and Henry at the Globe — and which now is clearly not the case with Kushner and the Register.

The Orange County meltdown was also the subject of an unusually nasty blog post earlier this month by Clay Shirky, who criticized Ryan Chittum of the CJR and Ken Doctor of Newsonomics and the Nieman Journalism Lab for overlooking the weaknesses in Kushner’s expansion. (Chittum and Doctor wrote detailed, thoughtful responses, and I’ve linked to both of them in the comments of a piece I wrote about the kerfuffle for WGBHNews.org.)

Arellano has gotten hold of some internal documents that make it clear that Kushner’s expansionary dreams were doomed from the start. He also paints a picture of a poisoned newsroom and offers lots of anonymous quotes to back it up.

“I wouldn’t say I got hoodwinked,” he quotes one former staff member as saying, “but it’s just another lesson of life: If it’s too good to be true, it is.”

I recently criticized Arellano for his overreliance on anonymous quotes, although I freely concede that I used them regularly when I was covering the media for The Boston Phoenix in the 1990s and the early ’00s. This time, he includes a clear explanation of why almost none of his sources would go on the record: fear of “reprisal or the endangerment of their buyout, which included a nondisclosure clause.” Given that, I think the story is stronger with the quotes than without.

Arellano writes:

In retrospect, it seems obvious Kushner set himself up for failure, like a Jenga tower depending on every precariously placed block. He installed himself as publisher despite having no previous newspaper experience. A hard paywall — his most controversial move — was erected to force readers to buy the print edition in an era when online content is king. To justify that, Kushner plunged into a hiring binge that saw the Register sign up hundreds of employees even though it didn’t have the revenue to pay them. To fund his vision, the sales department was tasked with selling all those points despite an industry-wide decline in print advertising during the past decade.

It’s a sad, ugly moment for a tale that began so optimistically. As for whether this will prove to be the end of the story — well, it sure looks that way, although Kushner insists he’s merely slowed down. After two years of hiring binges and layoffs, the launch and virtual folding of the Long Beach Register, and the inexplicably odd decision to start a Los Angeles Register to compete with the mighty Times, Kushner is clearly down to his last chance — if that.

The un-Muzzling of anti-abortion protesters

In 1999 I gave a Boston Phoenix Muzzle Award to Susan Fargo and Paul Demakis, two Massachusetts legislators pushing for an abortion-clinic buffer zone. Today the U.S. Supreme Court agreed, ruling that those buffer zones are an unconstitutional abridgment of the First Amendment.

Disruptive innovation and the future of news

Previously published at Medium.

Toward the end of The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton Christensen’s influential 1997 book about why good companies sometimes fail, he writes, “I have found that many of life’s most useful insights are often quite simple.”

Indeed, the fundamental ideas at the heart of his book are so blindingly self-evident that, in retrospect, it is hard to imagine it took a Harvard Business School professor to describe them for the first time. And that poses a problem for Jill Lepore, a Harvard historian who recently wrote a scathingly critical essay about Christensen’s theories for the New Yorker titled “The Disruption Machine.” Call it the Skeptic’s Dilemma.

Christensen offers reams of data and graphs to support his claims, but his argument is easy to understand. Companies generally succeed by improving their products, upgrading their technology, and listening to their customers — processes that are at the heart of what Christensen calls “sustaining innovations.” What destroys some of those companies are “disruptive innovations” — crude, cheap at first, attacking from below, and gradually (or not) moving up the food chain. The “innovator’s dilemma” is that companies sometimes fail not in spite of doing everything right, but because they did everything right.

Some examples of this phenomenon make it easy to understand. Kodak, focusing its efforts on improving photographic film and paper, paid no attention to digital technology (invented by one of its own engineers), which at first could not compete on quality but which later swallowed the entire industry. Manufacturers of mainframe computers like IBM could not be bothered with the minicomputer market developed by companies like Digital Equipment Corporation; and DEC, in turn, failed to adapt to the personal computer revolution led by the likes of Apple and, yes, IBM. (Christensen shows how the success of the IBM PC actually validates his ideas: the company set up a separate, autonomous division, far from the mothership, to develop its once-ubiquitous personal computer.)

Christensen has applied his theories to journalism as well. In 2012 he wrote a long essay for Nieman Reports in collaboration with David Skok, a Canadian journalist who was then a Nieman Fellow and is now the digital adviser to Boston Globe editor Brian McGrory, and James Allworth, a regular contributor to the Harvard Business Review. In the essay, titled “Breaking News,” they describe how Time magazine began in the 1920s as a cheaply produced aggregator, full of “rip-and-read copy from the day’s major publications,” and gradually moved up the journalistic chain by hiring reporters and producing original reportage. Today, they note, websites like the Huffington Post and BuzzFeed, which began as little more than aggregators, have begun “their march up the value network” in much the same way as Time some 90 years ago.

And though Christensen, Skok, and Allworth don’t say it explicitly, Time magazine, once a disruptive innovator and long since ensconced as a crown jewel of the quality press, is now on the ropes — cast out of the Time Warner empire, as David Carr describes it in the New York Times, with little hope of long-term survival.

***

INTO THIS SEA of obviousness sails Lepore, an award-winning historian and an accomplished journalist. I am an admirer of her 1998 book The Name of War: King Philip’s War and American Identity. Her 2010 New Yorker article on the Tea Party stands as a particularly astute, historically aware examination of a movement that waxes and wanes but that will not (as Eric Cantor recently learned) go away.

Lepore pursues two approaches in her attempted takedown of Christensen. The first is to look at The Innovator’s Dilemma as a cultural critic would, arguing that Christensen popularized a concept — “disruption” — that resonates in an era when we are all fearful of our place in an uncertain, rapidly changing economy. In the face of that uncertainty, notions such as disruption offer a possible way out, provided you can find a way to be the disruptor. She writes:

The idea of innovation is the idea of progress stripped of the aspirations of the Enlightenment, scrubbed clean of the horrors of the twentieth century, and relieved of its critics. Disruptive innovation goes further, holding out the hope of salvation against the very damnation it describes: disrupt, and you will be saved.

The second approach Lepore pursues is more daring, as she takes the fight from her turf — history and culture — to Christensen’s. According to Lepore, Christensen made some key mistakes. The disk-drive companies that were supposedly done in by disruptive innovators eating away at their businesses from below actually did quite well, she writes. And she claims that his analysis of the steel industry is flawed by his failure to take into account the effects of labor strife. “Christensen’s sources are often dubious and his logic questionable,” Lepore argues.

But Lepore saves her real venom for the dubious effects she says the cult of disruption has had on society, from financial services (“it led to a global financial crisis”) to higher education (she partly blames a book Christensen co-authored, The Innovative University, for the rise of massive open online courses, or MOOCs, of which she takes a dim view) to journalism (one of several fields, she writes, with “obligations that lie outside the realm of earnings”).

Christensen has not yet written a response; perhaps he will, perhaps he won’t. But in an interview with Drake Bennett of Bloomberg Businessweek, he asserts that it was hardly his fault if the term “disruption” has become overused and misunderstood:

I was delighted that somebody with her standing would join me in trying to bring discipline and understanding around a very useful theory. I’ve been trying to do it for 20 years. And then in a stunning reversal, she starts instead to try to discredit Clay Christensen, in a really mean way. And mean is fine, but in order to discredit me, Jill had to break all of the rules of scholarship that she accused me of breaking — in just egregious ways, truly egregious ways.

As for the “egregious” behavior of which he accuses Lepore, Christensen is especially worked up that she read The Innovator’s Dilemma, published 17 years ago, yet seems not to have read any of his subsequent books — books in which he says he continued to develop and refine his theories about disruptive innovation. He defends his data. And he explains his prediction that Apple’s iPhone would fail (a prediction mocked by Lepore) by saying that he initially thought it was a sustaining innovation that built on less expensive smartphones. Only later, he says, did he realize that it was a disruptive innovation aimed at laptops — less capable than laptops, but also cheaper and easier to carry.

“I just missed that,” he tells Bennett. “And it really helped me with the theory, because I had to figure out: Who are you disrupting?”

Christensen also refers to Lepore as “Jill” so many times that Bennett finally asks him if he knows her. His response: “I’ve never met her in my life.”

***

CHRISTENSEN’S DESCRIPTION of how his understanding of the iPhone evolved demonstrates a weakness of disruption theory: It’s far easier to explain the rise and fall of companies in terms of sustaining and disruptive innovations after the fact, when you can pick them apart and make them the subject of case studies.

Continue reading “Disruptive innovation and the future of news”

Why Rupert Murdoch probably won’t buy the Herald

Published earlier at WGBHNews.org.

Here’s the answer to today’s Newspaper Jeopardy question: “Maybe, if there’s a willing buyer and seller.”

Now for the question: “With Rupert Murdoch getting out of the Boston television market, is there any chance that he would have another go with the Boston Herald?”

Following Tuesday’s announcement that Cox Media Group would acquire WFXT-TV (Channel 25) from Murdoch’s Fox Television Stations as part of a Boston-San Francisco station swap, there has been speculation as to whether Murdoch would re-enter the Boston newspaper market. Universal Hub’s Adam Gaffin raises the issue here; the Boston Business Journal’s Eric Convey, a former Herald staff member, addresses it as well. I’ve also heard from several people on Facebook.

First, the obvious: There would be no legal obstacles if Murdoch wants to buy the Herald. The FCC’s cross-ownership prohibition against a single owner controlling a TV station and a daily newspaper in the same market would no longer apply.

Now for some analysis. Murdoch is 83 years old, and though he seems remarkably active for an octogenarian, I have it on good authority that he, like all of us, is not going to live forever. Moreover, in 2013 his business interests were split, and his newspapers — which include The Wall Street Journal, The Times of London and the New York Post — are now in a separate division of the Murdoch-controlled News Corp. No longer can his lucrative broadcasting and entertainment properties be used to enhance his newspapers’ balance sheets.

Various accounts portray Murdoch as the last romantic — the only News Corp. executive who still has a soft spot for newspapers. The Herald would not be a good investment because newspapers in general are not good investments, and because it is the number-two daily in a mid-size market. Moreover, the guilty verdict handed down to former News of the World editor Andy Coulson in the British phone-hacking scandal Tuesday suggests that Murdoch may be preoccupied with other matters.

On the other hand, who knows? Herald owner Pat Purcell is a longtime friend and former lieutenant of Murdoch’s, and if Rupe wants to stage a Boston comeback, maybe Purcell could be persuaded to let it happen. Even while owning the Herald, Purcell continued to work for Murdoch, running what were once the Ottaway community papers — including the Cape Cod Times and The Standard-Times of New Bedford — from 2008 until they were sold to an affiliate of GateHouse Media last fall.

There is a storied history involving Murdoch and the Herald. Hearst’s Herald American was on the verge of collapse in 1982 when Murdoch swooped in, rescued the tabloid and infused it with new energy. Murdoch added to his Boston holdings in the late 1980s, acquiring Channel 25 and seeking a waiver from the FCC so that he could continue to own both.

One day as that story was unfolding, then-senator Ted Kennedy was making a campaign swing through suburban Burlington. As a reporter for the local daily, I was following him from stop to stop. Kennedy had just snuck an amendment into a bill to deny Rupert Murdoch the regulatory waiver he was seeking that would allow him to own both the Herald and Channel 25 (Kennedy’s amendment prohibited a similar arrangement in New York). At every stop, Herald reporter Wayne Woodlief would ask him, “Senator, why are you trying to kill the Herald?”

The episode also led Kennedy’s most caustic critic at the Herald, columnist Howie Carr, to write a particularly memorable lede: “Was it something I said, Fat Boy?” Years later, Carr remained bitter, telling me, “Ted was trying to kill the paper in order to deliver the monopoly to his friends” at The Boston Globe.

Murdoch sold Channel 25, but in the early 1990s he bought it back — and sold the Herald to Purcell, who’d been publisher of the paper, reporting to Murdoch, for much of the ’80s. It would certainly be a fascinating twist on this 30-year-plus newspaper tale if Murdoch and Purcell were to change positions once again.

That’s Cox 25 to you

Here’s a late-afternoon bombshell for you: WFXT-TV (Channel 25) has been acquired by Cox Media Group, part of a station swap that will result in Fox owning two TV stations in San Francisco. Cynthia Littleton of Variety has the details.

I hope the move from Fox to Cox doesn’t harm the local news operation. Fox 25 News is one of the better-funded news organizations in Boston, with a fair number of people who are native to the area — including anchors Maria Stephanos and Mark Ockerbloom. Mike Beaudet, who’s joining our faculty this fall, is an award-winning investigative reporter.

Talking about ‘The Wired City’ in Rockport

I’ll be talking about “The Wired City” and the future of journalism this Wednesday, June 25, at 7 p.m. at the Rockport Public Library. If you’re in the area, I hope you’ll stop by.

Salem News fights for, gets documents in Chism case

If you think the public is entitled to know about the security arrangements (or lack thereof) for 15-year-old murder suspect Philip Chism, then you should thank The Salem News.

If you think the public is entitled to know about the security arrangements (or lack thereof) for 15-year-old murder suspect Philip Chism, then you should thank The Salem News.

Chism, charged with murdering Danvers High School teacher Colleen Ritzer, recently attacked a female youth worker at a detention center in Dorchester. The News went to court and asked that documents related to the case be released.

Today the News’ court reporter, Julie Manganis, writes that prosecutor Kate MacDougall had expressed concerns ahead of time that Chism should not be left alone with female staff. We also learn that Chism allegedly attacked the youth worker with a pencil, then “choked and beat her about the head.”

Even more alarming, MacDougall recently raised concerns about serious security lapses at the state’s Worcester Recovery Center and Hospital, where Chism is now being held.

The documents are online here.

This is important public-interest journalism, and it wouldn’t be possible if the News hadn’t been willing to devote legal resources to arguing for the release of the documents. The First Amendment requires that court proceedings be open to all. Good for the News, and good for Superior Court Judge Howard Whitehead, who ordered that the information be made public.