Previously published at WGBHNews.org.

A little less than two years ago, as Donald Trump was moving ever closer to wrapping up the Republican presidential nomination, Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos made a rather remarkable promise. “I have a lot of very sensitive and vulnerable body parts,” he said in a public conversation with the paper’s executive editor, Marty Baron. “If need be, they can all go through the wringer rather than do the wrong thing.”

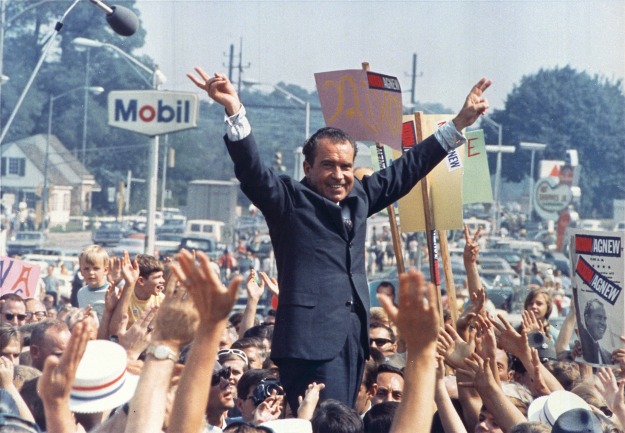

At the time, Trump was attacking the Post and Amazon, the retail behemoth that Bezos had founded, by threatening to launch an antitrust investigation and end Amazon’s (nonexistent) tax breaks. So Bezos’ promise carried with it a very specific meaning, especially for those steeped in Watergate lore. When Post reporter Carl Bernstein asked one of Richard Nixon’s thugs, John Mitchell, to comment on a particularly damaging story, Mitchell famously responded: “Katie Graham’s gonna get her tit caught in a big fat wringer if that’s published.” And here was Bezos, all those years later, pledging to stand tall in the face of threats from the powerful — as tall as Katharine Graham had in the 1970s. It was a promise that is now being put to the test.

President Trump, of course, has attacked the “fake news” media relentlessly. Last week, he turned his attention, as he sometimes does, to the Post.

In a subsequent tweet, Trump claimed that Bezos should be required to register the Post as a “lobbyist” for Amazon. He also referred to the paper as the “Fake Washington Post.” For those of us who are connoisseurs of such things, that’s a major improvement over his previous derogatory nickname, the “Amazon Washington Post,” though still not quite a match for the truly inspired “Failing New York Times.”

Of course, it’s easy to mock Trump. But his attacks on the Post go beyond buffoonery — they potentially represent real trouble. Imagine what would happen if the Trump administration launched an investigation into Amazon with the intent of harming the Post. The supine Republican Congress wouldn’t do anything but vaguely express concern. The Fox News-led right-wing media would bray for the Post’s demise.

And yet Trump isn’t Nixon. I don’t mean Trump isn’t as bad as Nixon; give him time, and he could prove to be worse. I mean that, stylistically, they are very different people with diametrically opposite ways of looking at the world. Nixon, for all his faults, fundamentally understood the legitimacy of the institutions he was seeking to undermine. He acted in secret, and the actions he considered taking against the Post — hitting the paper with a criminal complaint in order to undermine its public stock offering, challenging the licenses of the TV stations it held — would have hurt the Post in real, measurable ways.

By contrast, it’s hard to know how seriously to take Trump’s threats, based as they are on falsehoods so blatant that they can only be called lies. Amazon is not costing the post office money; it’s actually a boon. The Post is not a lobbyist for Amazon; Bezos has allowed the paper to operate independently, keeping his distance from both the news operation and the editorial pages. Trump is right about Amazon’s harming brick-and-mortar retailers, but it has paid state and local taxes just like any other company for some years now.

Also in contrast to Nixon’s skullduggery, Trump voices his threats in public. And that’s the key to what is really going on. Trump understands that in the current media environment, he doesn’t have to harm the business prospects of his enemies in the press (although Gabriel Sherman, writing in Vanity Fair, reports that he might try to go after the Post). He merely has to delegitimize them in the eyes of the 35 to 40 percent of the public that continues to support him. The Post, the Times, and other news organizations are benefiting from the “Trump effect,” as anti-Trump audiences are rewarding them not just with clicks but with paid subscriptions. Trump doesn’t care as long as he is able to convince his followers that he and his sycophants at Fox News and Breibart are the source of all the reality that they need.

In the closing weeks of the 2016 campaign, at a time when it looked like Trump was going to lose, Bezos spoke out against Trump for suggesting he wouldn’t respect the results of the election unless he won. “One of the things that makes this country so amazing is that we are allowed to criticize and scrutinize our elected leaders,” Bezos said. “There are other countries where if you criticize the elected leader you might go to jail. Or worse, you may just disappear.”

In fact, Trump is making his enemies in the media disappear — not to all of us, and certainly not to the majority who are appalled by his presidency. But he is making the mainstream media disappear to his followers and replacing them with himself as the ultimate arbiter of reality. The Fake Washington Post and the Failing New York Times aren’t going anywhere. For the Trump minority, though, they have ceased to exist.