![]() There’s good news about local news in Greater Boston today on three fronts. I’ll start with an attempt to revive arts reviews — at one time a staple of mainstream and alternative publications, but now relegated to niche outlets like The Arts Fuse, a high-quality website edited by Boston University professor and former Boston Phoenix arts writer Bill Marx.

There’s good news about local news in Greater Boston today on three fronts. I’ll start with an attempt to revive arts reviews — at one time a staple of mainstream and alternative publications, but now relegated to niche outlets like The Arts Fuse, a high-quality website edited by Boston University professor and former Boston Phoenix arts writer Bill Marx.

Recently Paul Bass, the executive director of the nonprofit Online Journalism Project in New Haven, Connecticut, launched a grant-funded project called the Independent Review Crew (link now fixed). Freelancers in seven parts of the country are writing about music, theater and other in-person cultural events. Boston is among those seven, and freelance writer-photographer Sasha Patkin is weighing in with her take on everything from concerts to sand sculpture.

You can read Patkin’s work on the Review Crew’s website — and, this week, her reviews started running on Universal Hub as well, which gives her a much wider audience. Here’s her first contribution.

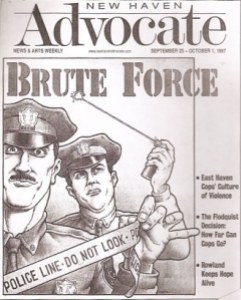

Bass is the founder of the New Haven Independent, started in 2005 as part of the first wave of nonprofit community websites. The Online Journalism Project is the nonprofit umbrella that publishes the Indy and a sister site in New Haven’s northwest suburbs; it also oversees a low-power radio station in New Haven, WNHH-LP. Before 2005, Bass was a fixture at the now-defunct New Haven Advocate, an alt-weekly that, like the Phoenix, led with local arts and was filled with reviews. The Review Crew is his bid to revive the long lost art, if you will, of arts reviewing.

Other places that are part of The Review Crew: New Haven; Tulsa, Oklahoma; Troy/Albany, New York; Oakland, California; Hartford, Connecticut; and Northwest Arkansas (the Fayetteville metro area is home to about 576,000 people).

I’ve got all kinds of disclosures I need to share here. I gave Bass some guidance before he launched The Review Crew — not that he needed any. The Indy was the main subject of my 2013 book “The Wired City,” and I’ve got a lengthy update in “What Works in Community News,” the forthcoming book that Ellen Clegg and I have written. I also suggested Universal Hub to Bass as an additional outlet for The Review Crew; I’ve known Gaffin for years, and at one time I made a little money through a blogging network he set up. Gaffin was a recent guest on the “What Works” podcast.

In other words, I would wish Paul the best of luck in any case, but this time I’ve got a bit more of a stake in it.

***

The Phoenix was not the city’s last alt-weekly. For nearly a decade after the Phoenix shut down in 2013, DigBoston continued on with a mix of news and arts coverage. Unfortunately, the Dig, which struggled mightily during COVID, finally ended its run earlier this year. But Dig editors Chris Faraone and Jason Pramas are now morphing the paper into something else — HorizonMass, a statewide online news outlet. Pramas will serve as editor-in-chief and Faraone as editor-at-large, with a host of contributors.

The Phoenix was not the city’s last alt-weekly. For nearly a decade after the Phoenix shut down in 2013, DigBoston continued on with a mix of news and arts coverage. Unfortunately, the Dig, which struggled mightily during COVID, finally ended its run earlier this year. But Dig editors Chris Faraone and Jason Pramas are now morphing the paper into something else — HorizonMass, a statewide online news outlet. Pramas will serve as editor-in-chief and Faraone as editor-at-large, with a host of contributors.

HorizonMass will publish as part of the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism, founded by Faraone and Pramas some years back to funnel long-form investigative coverage to a number of media outlets, including the Dig. HorizonMass will also have a significant student presence, Pramas writes, noting that the project’s tagline is “Independent, student-driven journalism in the public interest.” Pramas adds:

With interns working with us as reporters, designers, marketers, and (for the first time) editors, together with our ever-growing crew of professional freelance writers, we can continue to do our part to train the next generation of journalists while covering more Bay State happenings than ever before. We hope you enjoy our initial offerings and support our efforts with whatever donations you can afford.

***

Mark Pothier, a top editor at The Boston Globe, is leaving the paper to become the editor and CEO of the Plymouth Independent, a well-funded fledgling nonprofit. Pothier, a longtime Plymouth resident and former musician with the band Ministry, is already listed on the Independent’s masthead. Among the project’s advisers is Boston Globe journalist (and my former Northeastern colleague) Walter Robinson, also a Plymouth resident, who was instrumental in the launch of the New Bedford Light. Robby talked about the Plymouth Independent and other topics in a recent appearance on the “What Works” podcast.

Mark Pothier, a top editor at The Boston Globe, is leaving the paper to become the editor and CEO of the Plymouth Independent, a well-funded fledgling nonprofit. Pothier, a longtime Plymouth resident and former musician with the band Ministry, is already listed on the Independent’s masthead. Among the project’s advisers is Boston Globe journalist (and my former Northeastern colleague) Walter Robinson, also a Plymouth resident, who was instrumental in the launch of the New Bedford Light. Robby talked about the Plymouth Independent and other topics in a recent appearance on the “What Works” podcast.

Pothier started working at the Globe in 2001, but before that he was the executive editor of a group of papers that included the Old Colony Memorial, now part of the Gannett chain. When Gannett shifted its Eastern Massachusetts weeklies to regional coverage in the spring of 2022, the Memorial was one of just three that was allowed to continue covering local news — so it looks like Plymouth resident are about to be treated to something of a news war.

The

The  Why does it matter for a community to have a variety of journalistic voices? We could all point to any number of examples. But the example I want to discuss here is a story about brain cancer among Pratt & Whitney employees in Greater New Haven.

Why does it matter for a community to have a variety of journalistic voices? We could all point to any number of examples. But the example I want to discuss here is a story about brain cancer among Pratt & Whitney employees in Greater New Haven.