I knew that the news staff at Boston 25 was getting squeezed, but I didn’t realize how deeply until I read Aidan Ryan’s report in The Boston Globe (I’m briefly quoted). Ryan writes:

… at least 13 staffers, including reporters, producers, salespeople, and a news director, who have left the station since the start of the year, according to interviews and workers’ LinkedIn profiles. Those exits at WFXT-TV (Channel 25) came on top of a steady trickle of departures stretching back years.

Eight current and former employees who spoke to the Globe cited a confluence of factors driving people out, including issues with the quality of the station’s content, overwhelming workloads, pay cuts, layoffs, and uncertainty over whether its private equity owners will keep the lights on. Most spoke on condition of anonymity because of fears of retribution.

You will not be surprised to learn that many of these cuts coincide with the station’s 2019 acquisition by a private equity firm, Apollo Global Management. Private equity has destroyed much of the journalistic landscape, especially local newspapers. Unlike newspapers, though, local television news is still a fairly lucrative business, as well as where a large proportion of Americans get their news, according to the Pew Research Center. If you look at this chart, you’ll see that advertising revenues have held fairly steady, with increases in digital offsetting some of the decline in over-the-air ads.

Private equity firms and hedge funds, though, care about only one thing: how much profit they can wring out before walking away and letting the next owner clean up the mess. In fact, Ryan reports that Apollo tried to sell Boston 25 to another hedge fund in 2022, but that deal fell through.

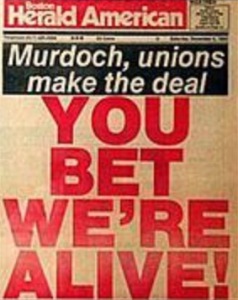

Boston 25 — formally WFXT-TV (Channel 25) — has a long history tied up in the convoluted tale of Rupert Murdoch’s one-time ownership of the Boston Herald. As I wrote for GBH News back in 2014, Hearst’s Herald American was on the verge of collapse in 1982 when Murdoch swooped in, rescued the tabloid and infused it with new energy. Murdoch added it to his Boston holdings in the late 1980s, acquiring Channel 25 and seeking a waiver from the FCC so that he could continue to own both.

One day as that story was unfolding, then-Sen. Ted Kennedy was making a campaign swing through suburban Burlington. As a reporter for the local daily, I was following him from stop to stop. Kennedy had just snuck an amendment into a bill to deny Murdoch the regulatory waiver he was seeking that would allow him to own both the Herald and Channel 25 (the amendment prohibited a similar arrangement in New York). At every stop, Herald reporter Wayne Woodlief would ask him, “Senator, why are you trying to kill the Herald?”

The episode also led Kennedy’s most caustic critic at the Herald, columnist Howie Carr, to write a particularly memorable lead: “Was it something I said, Fat Boy?” Years later, Carr remained bitter, telling me, “Ted was trying to kill the paper in order to deliver the monopoly to his friends” at The Boston Globe.

As a result of Ted Kennedy’s amendment, Murdoch sold the Herald to his longtime protégé Pat Purcell, who operated it until 2018, when the paper declared bankruptcy and was delivered unto the hands of Alden. Murdoch, meanwhile, continued to operate Fox 25.

In those days Fox 25 was a well-staffed operation with a real Boston flavor, running a satellite bureau across the street from the Statehouse and featuring segments such as “The Heavy Hitters” — commentary by local media guys Peter Kadzis, Cosmo Macero and Doug Goudie. Among the station’s journalists were anchor Maria Stephanos and investigative reporter Mike Beaudet, both of whom are now at WCVB-TV (Channel 5). Mike is also a colleague at Northeastern University. And no, despite Murdoch’s involvement, the station bore no resemblance to the Fox News Channel.

The station was acquired by Cox Media Group in 2014, and the station slowly became less distinctive and more generic. “The Heavy Hitters” was eliminated, as was the Beacon Hill bureau. Cutting began and then accelerated after Cox sold itself to Apollo in 2019. That said, I still like what I see whenever I tune in the Boston 25 newscast, and I hope there’s a way forward. Anchor-reporter Kerry Kavanaugh has been generous in helping us with several mayoral debates in Medford.

Boston is fortunate to still have a number of local TV newscasts, and some of them are quite good. Still, the fading away of Boston 25 is sad as well as a loss for both the community and the people who work there — and for those who are no longer at the station.

Correction: Updated to note that Doug Goudie was one of “The Heavy Hitters.” I had the wrong Doug.