By Bill Kirtz

By Bill Kirtz

“Revel in hardship,” NPR’s Beirut-based correspondent Kelly McEvers told last weekend’s annual narrative journalism conference at Boston University. “Don’t despair if you have a scarcity of resources.”

Sneaking into danger zones where sources were too terrified to speak, the award-winning reporter has spent the past two years covering the Arab Spring uprisings, producing vivid stories with ambient sound, protective descriptions and a remote network of dissidents.

International photographer Alan Chin echoed her comments. He’s an editor at Newsmotion.org, a Kickstarter-funded collation of amateur and professional voices and video that focuses on undercovered human-rights stories. As traditional journalism faces financial crises, “we have to take chances…. We can’t just sit around” complaining about our problems, Chin said. “We have to absolutely be willing to fail.”

Newsmotion founder Julian Rubinstein, a prize-winning magazine and book author, hopes the site offers insight that deadline-driven traditional outlets often neglect.

And narrative journalism’s goal is insight, using fiction’s tools to create compelling scenes — with one huge distinction. Every detail must be as accurate and well documented as in the best investigative reporting. Mitch Zuckoff and Dick Lehr answer the perennial “How did the author know this?” question with 30 to 40 pages of endnotes verifying every detail.

The two, who won several reporting prizes at the Boston Globe and who now teach at Boston University with conference organizer and narrative journalism exemplar Mark Kramer, stressed that point with examples from their latest books.

For Zuckoff, the challenge is to tell an important story in the “richest possible way” — not “lecturing to people,” but drawing them into a complex history. In “Frozen in Time,” he weaves a World War II search-and-survival story into recent attempts to locate a long-missing rescue plane.

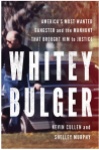

Lehr followed the traditional reporter’s dogged tactic of never abandoning the fight to get documents about mobster James “Whitey” Bulger. After years of trying, he found a “treasure trove” of prison files to use in his co-authored “Black Mass,” which chronicles the FBI’s corrupt ties to the fugitive killer.

Narrative journalism doesn’t take years’-long immersion in a story, noted Amy Ellis Nutt. Although she won a Pulitzer Prize ago for a 20-page Newark (N.J.) Star-Ledger feature series, she said she’s now a big fan of “miniatures.”

Why? “We don’t live life in long narrative span, [so] short is natural,” she said. “You [can] just jump in the middle.”

To make her point, Nutt cited Ernest Hemingway’s ability to tell a dramatic tale in six words: “For Sale. Baby Shoes. Never Worn.” One of her recent narratives, which starts by saying it was “too cold even for the seagulls,” delivers precise description in relatively few words.

Neil Shea, a BU lecturer and award-winning war reporter, has also turned to short-form narrative. He said that conventional coverage of such familiar topics as Afghanistan can become “background noise” for news consumers. So he’s doing regular 300- to 1,100-word vignettes of colorful dialogue and scenes without overwhelming readers with context.

Shea was one of several speakers who underscored the need to prune excess material ruthlessly.

“We have to be merciless self-editors,” he said. When considering using the first person, he said, ask yourself, “Do I really need to be in this story?”

Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter Rosalind Bentley advises cutting anything, no matter how compelling, if it doesn’t support the story’s main thesis. She pored through the 500-page trial transcript after the poet Natasha Trethewey’s stepfather killed her mother to winnow out just this detail: “She died on the pavement.”

Any quote she uses “has to sparkle like the Hope diamond.” If it doesn’t, she’ll paraphrase.

“You can’t just wing it and start writing,” she said. “All your choices have to be deliberate.” So she wields multi-colored highlighters over pages of scrawled notes to boil down the essence of a story in one sentence, and then just one word.

In her definitive profile of Trethewey, the word was “self-definition.”

Why do narrative journalists keep plugging along in an age of economic uncertainty and audience fragmentation?

Author, magazine founder and University of California Berkeley journalism professor Adam Hochschild put it this way: “When you tell a story, it takes on a life of its own and sometimes it affects people.”

He said “Bury the Chains,” his 2005 account of how a few men started a movement to free the slaves in the British Empire, got good reviews, many awards and decent initial sales — then languished on remainder shelves for years.

But recently, Hochschild started getting speaking invitations from global-warming groups, who saw his 18th-century abolitionists as a model of how a few people could change how the world thinks about an issue.

His point: “A story can come bouncing back to you.”

Bill Kirtz is an associate professor of journalism at Northeastern University in Boston.