We vote at the Holten-Richmond Middle School in Danvers, home of Precincts 1 and 2. I cast my ballot at about 9:45 a.m., and was the 407th person in Precinct 1 to do so. The polls are open until 8 p.m. Get out and vote!

By Dan Kennedy • The press, politics, technology, culture and other passions

I have a simple reason for voting against Question 2, the “Death with Dignity” referendum, which would, if passed, legalize physician-assisted suicide in Massachusetts. People in the disability-rights movement who I respect are against it. And I agree with their reasoning.

Unlike other people you may have heard from on both sides of the question, I do not have any heartbreaking or poignant stories to share. Rather, I have a perspective that I gained a decade ago when I was researching my first book, “Little People.”

Among other things, I learned disability-rights activists worry that advances in medical technology are making it increasingly easy to diagnose genetic conditions in utero — thereby leading to the likelihood that parents will select abortion, even in cases (such as dwarfism) where the disability is not particularly severe or incompatible with what society considers to be a “normal” life.

Indeed, my wife and I encountered that attitude ourselves when our then-infant daughter saw a geneticist who wanted us to know there was nothing that could have been done. What she meant was that Becky’s dwarfism couldn’t have been diagnosed in utero (it could today), and thus we shouldn’t feel bad that we weren’t given a chance to choose abortion.

We were shocked, but I guess we shouldn’t have been. And in researching “Little People,” I learned from the geneticist Dorothy Wertz (pdf) that many people would choose abortion if they were told their child would be a dwarf — and, significantly, that medical professionals were more pro-abortion than lay people.

That’s the attitude disability-rights activists are worried about with regard to Question 2: a negative approach toward people who are sick or disabled, and who might be pressured into choosing suicide by family, insurance companies and doctors. And that’s why I’m voting no.

I urge you to read a truly moving essay in this week’s Phoenix by S.I. Rosenbaum, and to listen to an interview that was broadcast in September by WBUR Radio (90.9 FM) with disability-rights activist John Kelly, who opposes Question 2, and Dr. Marcia Angell, who’s for it. You can also learn more about the reasons for opposing physician-assisted suicide at Second Thoughts. The argument in favor is available at Death with Dignity.

What follows is an excerpt from “Little People” dealing with research about attitudes about disability and abortion.

***

I interviewed Dorothy Wertz, a psychiatrist affiliated with the Eunice Kennedy Shriver Center in Waltham, on a cold February day in the sunroom of her home on Massachusetts’s South Coast. Her husband was dying of lung cancer. She would die a year later. Nevertheless, she cut a flamboyant figure, tall and with a strong physical presence despite her advanced years, wearing a pillbox hat, turquoise earrings, and an enormous silver-and-turquoise necklace that looked heavy enough to weigh her down. I’d met her years earlier when I took part in a study she’d overseen regarding the attitudes that parents of disabled kids hold toward the medical establishment. I liked her forthright, down-to-earth manner. What I didn’t like so much was what she had learned about attitudes toward disability — including dwarfism.

In the late 1990s Wertz conducted a study of about two thousand people — 1,084 genetics professionals, 499 primary-care physicians, and 476 patients. One of the disabilities that participants were questioned about was achondroplasia, the most common form of dwarfism. The results were stunning. Among the genetics professionals, 57 percent would choose abortion if it were detected in utero; among physicians, 29 percent; and among patients, 24 percent.

To bracket this, let me pull out two other findings. The first pertains to Down syndrome, certainly a serious genetic condition, but one not incompatible with a good quality of life. Here the proportion of genetics professionals who would abort was 80 percent; physicians, 62 percent; and patients, 36 percent. The second involves a genetic predisposition to severe obesity, which is not a disability at all, or even destiny. After all, parents can teach their kids to eat properly and lead healthy, active lives. Yet even in this instance, 29 percent of genetics professionals would choose to abort, as well as 13 percent of physicians and 8 percent of patients.

What’s frightening about all of this is that we are closer to screening for such conditions on a routine basis than many people realize. Some day — perhaps in a decade, perhaps two or three — it will be possible to lay out a person’s entire DNA on a computer chip, all thirty thousand or so genes, and compare that person’s DNA to the ideal. Such chips could be generated for early-term fetuses just as easily as for those already born. Once the use of such technology becomes routine, it would cost “mere pennies per test,” as Wertz has written, to screen fetuses for thousands of genetic conditions. Including, of course, achondroplasia and several other types of dwarfism.

Wertz’s study points to another potential concern. Across the board, her findings show that ordinary people are far less likely to choose abortion than are medical professionals. (To be sure, one in four ordinary couples would choose abortion if they learned their child would have achondroplasia, which is high by any measure.) Yet it is medical professionals who will counsel couples when they learn that the child they are expecting would have a disability. What kind of pressure will these professionals use to obtain what is, to some of them, the preferable result? If we had learned the fetus Barbara was carrying in the early spring of 1992 would have severe respiratory problems and could have a whole host of other complications as well, what would we have chosen to do? There was no Becky at that point, only a possibility. And the possibility would have sounded more frightening than hopeful.

Little People of America has long argued that prospective parents who learn that their child will have a type of dwarfism should be provided with information about the good lives that most dwarfs lead, and even be given a chance to meet dwarf children and adults. It’s a great idea. But will it happen? And at a time of skyrocketing medical costs, are there too many social pressures against that happening? There’s no doubt that, in many instances, abortion would be in the best interest of insurance companies. Think of all the money they could save if they refused to cover a fetus that has been diagnosed with a potentially expensive genetic condition. Some parents, of course, would not choose abortion because of their religious or moral beliefs. But what about the vast majority of us — the people who regularly tell pollsters that they’re pro-choice, although they may be deeply uncomfortable with abortion personally? Would they be able to resist — would they, should they, even attempt to resist — when faced with the possibility of financial ruin?

And abortion is just one part of this, a crude, archaic approach that will likely fade away with improvements in medical technology — improvements that will raise few of the moral qualms that so divide the culture today. For instance, when you think about it, sex is a really messy, random way of reproducing. Sure, it’s fun. But look at all the things that can and do go wrong. In his book Redesigning Humans, Gregory Stock argues that in vitro fertilization will someday be seen as the only proper way to have children. “With a little marketing by IVF clinics,” he writes, “traditional reproduction may begin to seem antiquated, if not downright irresponsible. One day, people may view sex as essentially recreational, and conception as something best done in the laboratory.”

Even average-size couples who wouldn’t abort a fetus with achondroplasia would, in all likelihood, choose against implanting an embryo with the mutation. You’ve got five embryos in that Petri dish over there, and you can only implant one. This one has the genetic mutation for Down syndrome; that one has the mutation for achondroplasia; the other three are mutation-free. All right, which one do you think should be implanted?

And thus we will take another step down the road toward the “new eugenics” — a road that, in Stock’s utopian vision, will include artificial chromosomes to include spiffy new designer genes that will protect our descendants from disease, help them to live longer, and make them smarter, better, happier, and just generally imbued with oodles of wonderfulness.

Ultimately Stock posits a world in which we’re going to eliminate achondroplasia and hundreds, if not thousands, of other genetic conditions, predispositions, and tendencies. And we’re going to do it either by eliminating any individual whose genes we don’t like — or we’re going to change the genes.

I’m often frustrated with Boston Globe editorials because they avoid strong stands and take both sides of every issue. So I thought it was interesting that its endorsement of Elizabeth Warren was so unstinting, with little good to say about Sen. Scott Brown.

After recounting Brown’s unproven assertions that Warren took professional advantage of her undocumented Native American ancestry, the editorial includes this very tough line: “By campaigning on his personality, rather than his abilities, Brown seems to be bucking for his own form of affirmative action.”

No question the Globe was going to endorse Warren. But I wonder if it might have been a little more nuanced if Brown hadn’t taken a torch to his nice-guy image.

President Barack Obama’s commanding performance in the third and final debate mattered to the viewers at home, of course. But as we will see in the days ahead, it will matter even more in setting the tone for how the media will cover the campaign in the final run-up to the election.

Pay no attention to the silly pronouncements coming from Gov. Mitt Romney’s side — such as Bret Stephens’ analysis in the Wall Street Journal that Romney succeeded by coming across as “a perfectly plausible president.”

In fact, Romney’s timid me-too rhetoric on issues over which he’d been hammering Obama for months played poorly with the public. New York Times polling expert Nate Silver averaged the instant polls coming out of Monday night’s debate and found that Obama did even better than he had in the second one — a 16-point spread, compared to just 10 points a week ago.

Several hundred thousand of my close friends and I will be live-tweeting the presidential debate. I’m at @dankennedy_nu. I’ll also be contributing to the Fox 25 News live blog at www.myfoxboston.com. Hope you’ll chime in.

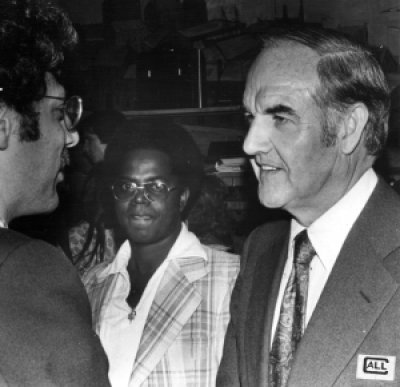

George McGovern was the only presidential candidate I ever worked for. In the fall of 1972 I was a 16-year-old junior at Middleborough (Mass.) High School and a McGovern volunteer. Mainly I made calls to supposedly undecided voters, and was informed by more than one that I was working for a “communist.”

George McGovern was the only presidential candidate I ever worked for. In the fall of 1972 I was a 16-year-old junior at Middleborough (Mass.) High School and a McGovern volunteer. Mainly I made calls to supposedly undecided voters, and was informed by more than one that I was working for a “communist.”

McGovern was one of the most decent people ever to seek the presidency, and I was sorry to learn of his passing this morning. I don’t know what kind of a president he would have been — I suspect he would have made Jimmy Carter look like a decisive executive by comparison. But he had a war hero’s aversion to war, and his generous spirit would have been welcome qualities in any of the presidents elected since his failed 1972 campaign. Needless to say, he would have been vastly superior to Richard Nixon, who defeated him in that historic landslide.

In April 1978, when I was a Northeastern co-op student working at the Woonsocket (R.I.) Call, I covered a speech McGovern gave in Boston, and took the photo you see here. It would probably take me half a day to find the clip, and it wouldn’t be of much account anyway. But I had just read Hunter S. Thompson’s “Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72,” and I remember asking McGovern if Thompson’s description of McGovern’s reasoning for dropping Thomas Eagleton from the ticket was accurate.

McGovern paused a moment, and then confirmed Thompson’s account. I thought it was a remarkable admission. Thompson had written that McGovern believed Eagleton’s mental illness was so severe that he had concluded he couldn’t run the risk of his becoming vice president — or, possibly, president. In 2005, McGovern told the New York Times: “I didn’t know a damn thing about mental illness, and neither did anyone around me.”

The last time I saw McGovern was in 1984, four years after he had been defeated for re-election to the Senate. He was running for president again and was taking part in a debate among the Democratic candidates. It might have been at Harvard, but I’m not entirely sure. It seemed that time had passed him by, and indeed he wasn’t a factor in what turned out to be a two-man race between Walter Mondale and Gary Hart.

During the debate, McGovern sharply criticized the federal government’s decision to break up the AT&T monopoly two years earlier. Even then, it seemed like an old man’s lament. With the passage of time, it became clear that the break-up unleashed technological innovation that wouldn’t have otherwise been possible. McGovern’s era was over, as even liberal Democrats had moved on.

After that, McGovern faded from view. It is to Bill Clinton’s credit that he gave the former senator useful work, and awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Still, his declining years could not have been happy ones, as he lost two of his adult children following long struggles with alcohol abuse.

George McGovern was one of the great public figures of the second half of the 20th century. Simply put, he showed us all a better way. It was not his fault that we chose not to take it. And now his voice has been stilled.

Update: You’re going to see a lot of fine tributes to McGovern in the days ahead. This one, by Joe Kahn of the Boston Globe, is well worth your time.

In claiming that President Obama was not fully truthful last night regarding when he said he labeled the attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya, an “act of terror,” the fact-checkers are adopting as their own the manner in which Gov. Mitt Romney wants to frame it. The attack claimed several American lives, including that of Ambassador Christopher Stevens.

In claiming that President Obama was not fully truthful last night regarding when he said he labeled the attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya, an “act of terror,” the fact-checkers are adopting as their own the manner in which Gov. Mitt Romney wants to frame it. The attack claimed several American lives, including that of Ambassador Christopher Stevens.

When the exchange took place, Romney appeared to be wildly, extravagantly wrong in claiming it took Obama two weeks to utter those words. He never fully regained his composure after moderator Candy Crowley read a transcript in which Obama, in a Rose Garden address the day after the attack, spoke of it in the context of “acts of terror.”

And it turns out that Obama said it again two days later: “I want people around the world to hear me: To all those who would do us harm, no act of terror will go unpunished.”

Hard to be much clearer than that. Yet look at how some of the leading fact-checkers handled it.

• PolitiFact, on Obama’s insistence that he labeled it an “act of terror” right from the beginning: “Obama described it in those terms the day after the attack. But in the days that followed, neither he nor all the members of his administration spoke consistently on the subject. There were many suggestions that the attack was part of demonstrations over an American-made video that disparaged Islam. We rate the statement Half True.”

• FactCheck.org, on Romney’s claim that it took Obama withheld the terrorism label for two weeks: “Romney isn’t entirely wrong. Romney claimed Obama refused for two weeks after the Benghazi attack to call it a terrorist attack and, instead, blamed it on a spontaneous demonstration in response to an anti-Muslim video that earlier that day triggered a violent protest in Egypt.”

• The Washington Post: “Romney’s broader point is accurate — that it took the administration days to concede that the assault on the U.S. mission in Benghazi was an ‘act of terrorism’ that appears unrelated to initial reports of anger at a video that defamed the prophet Muhammad. (The reporting is contradictory on whether there was indeed a demonstration outside the mission.) By our count, it took eight days for an administration official to concede that the deaths in Libya were the result of a ‘terrorist attack.'”

It’s pretty easy to see what’s going on here. Romney has attempted to frame the issue as though any suggestions from the White House that the attack may have had something to do with the inflammatory video “Innocence of the Muslims” are incompatible with Obama’s statements that the attack was an “act of terror.”

But why should that be so? Why are they mutually exclusive? Obama said from the start that the attack was an “act of terror,” he repeated it and he hasn’t wavered on it. The administration has wavered on what role the video might have played. It’s worth noting that the New York Times, which had people on the ground in Benghazi, stands by its reporting that the anger stirred up by the video actually did play into the attack. The terrorist attack, if you will.

The administration’s response to the Benghazi attack has not been a shining moment, and Romney had plenty to work with. So it was obviously a huge mistake on Romney’s part for him instead to dwell on whether and when Obama labeled it an “act of terror” rather than focusing on the reasons for the security breakdown and shifting explanations for what went wrong.

But thanks to the fact-checkers’ genetic disposition to throw a bone to each side regardless of the truth, Romney’s mistake looks less damaging today than it did last night.

Photo (cc) by Cain and Todd Benson and republished under a Creative Commons license. Some rights reserved.

I’ll be talking about the presidential debate tonight at 10:30 on Fox 25 News with Maria Stephanos. There may be some Web chatting during the debate as well. If you’d like to join in, I’ll post details here on Twitter.

This is pretty bad. In a profile of Stephanie Cutter, President Obama’s deputy campaign manager, the New York Times repeats a demonstrably false allegation advanced by Paul Ryan and others. Times reporter Amy Chozick writes:

Ms. Cutter doesn’t always stick to the talking points. In a recent CNN interview, she said Mr. Romney’s tax cuts “stipulated, it won’t be near $5 trillion,” as the Obama campaign had earlier claimed. The gaffe became fodder for a Romney attack ad three days later and was raised by Representative Paul D. Ryan in the vice-presidential debate on Thursday night.

Chozick links to the transcript of Cutter’s exchange with CNN’s Erin Burnett, but apparently she didn’t bother to read it; the headline, “Cutter Concedes $5 Trillion Attack on Romney Is Not True,” is simply wrong. Because here’s what Cutter actually said: the tax cut could be a lot less than $5 trillion if Romney closes loopholes and ends deductions; but Romney hasn’t specified any; therefore, yes, it’s a $5 trillion tax cut.

“The math does not work with what they’re saying,” Cutter told Burnett. “And they won’t name those deductions, not a single deduction that they will close because they know that is bad for their politics…. Last night, he [Romney] walked away from it, said he didn’t have a $5 trillion tax cut. He does.”

I wrote about this last week for the Huffington Post.

The controversy over compounding pharmacies is now crossing into the U.S. Senate race between Republican incumbent Scott Brown and Democratic challenger Elizabeth Warren. Hard to say where this might lead, but it’s worth keeping an eye on.

First up: Noah Bierman and Frank Phillips report in the Boston Globe that Brown backed an effort by the compounding-pharmacy industry to stop the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration from imposing new regulations. Brown also received $10,000 in donations from a fundraising event organized by the owner of the New England Compounding Center in Framingham, ground zero in the meningitis outbreak.

That sounds pretty bad. But Brown’s explanation — that he and the industry wanted a rule requiring drugs to be delivered directly to doctors rather than patients — seems reasonable.

“As you know, they sometimes fall into the wrong hands,” Brown told the Globe. “I was advocating getting it to the doctors, which I don’t think loosens regulations.”

Next up is the Boston Herald, whose reporter Erin Smith writes today that, in 2007, Sen. Ted Kennedy pushed for exactly the kind of tough regulations and DEA oversight that might have prevented the meningitis cases.

Again, it’s hard to know how that might be relevant to the Brown-Warren race. But the Herald story describes an industry flat-out opposed to any federal involvement.

“They have a huge amount of lobbyists. They give money to politicians. We didn’t have that,” Arthur Levin, director of the Center for Medical Consumers, told the Herald. “Sen. Ted Kennedy had a lot of influence, but obviously the bill didn’t get enough support.”

If nothing else, the Herald story casts the industry’s more recent efforts, supported by Brown, in a less benign light. And given that Brown holds Kennedy’s old seat, it could make for an irresistible compare-and-contrast.

I doubt we’ve heard the last of this.

Photo (cc) by Brian Finifter and republished under a Creative Commons license. Some rights reserved.