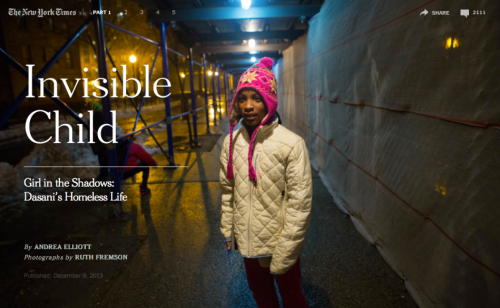

I finished this today. My God. I am just blown away. I decided to take it a day at a time even though the whole thing had been posted earlier in the week. I found myself hoping it would end on an optimistic note. Spoiler alert: it did.

Tag: New York Times

Some worthwhile online videos about Nelson Mandela

Since learning of Nelson Mandela’s death a few hours ago, I’ve watched:

- The New York Times’ excellent video overview of his life.

- The speech he gave after his release from prison.

- A report from WGBH-TV’s old “Ten O’Clock News” on Mandela’s 1990 visit to Roxbury.

- A clip from an interview Mandela did with Bill Moyers in 1991.

- And, for good measure, Artists Against Apartheid’s video for “Sun City.” Where else can you see Miles Davis, Lou Reed and Miami Steve in one (virtual) place?

What I haven’t watched is any television coverage. It’s a new world, isn’t it?

Michael Calderone on what to expect from Carolyn Ryan

One of the first media pieces I ever wrote for The Boston Phoenix, in the mid-1990s, was on the shrinking Statehouse press corps. Among those I interviewed was a young reporter for The Patriot Ledger of Quincy named Carolyn Ryan.

Ryan went on to great success at the Boston Herald, The Boston Globe and The New York Times. She was recently named the Times’ Washington bureau chief, and Michael Calderone of The Huffington Post has written about what to expect. An excerpt:

Ryan … has managed large reporting staffs in New York and Boston and is known inside the paper as a fierce competitor who sets high expectations. Such attributes can benefit the the Times’ Washington operation, which appears to be stepping up efforts against Politico and others in driving the political conversation of the day. Ryan may help ward off the complacency that news outlets long at the top of the media pecking order can sometimes fall prey to.

Quite a rise for Ryan, a hard-working, talented journalist. She deserves this moment, and I have no doubt she’ll make the most of it.

The New York Times and the Holocaust

Filmmaker Emily Harrold visited Northeastern on Thursday for a screening of “Reporting on The Times,” which explores how The New York Times covered (and didn’t cover) the Holocaust. Her film is based on Northeastern journalism professor Laurel Leff’s book “Buried by The Times.”

Click here for my Storify on the screening and the panel discussion that followed.

Why John Henry should dump Times content

The New York Times Co. no longer owns The Boston Globe. Now is the moment for new owner John Henry to take the next step: stop running Times content in his paper.

The New York Times Co. no longer owns The Boston Globe. Now is the moment for new owner John Henry to take the next step: stop running Times content in his paper.

I’m suggesting this not because I dislike the Times. Rather, I’m suggesting it because the Globe’s best, most engaged readers are those who are most likely to read the Times, too. There’s nothing quite like reading the Globe and coming across a shortened Times story on a national or international event to make you feel like you’re reading Times Lite.

For example: The story above, by New York Times reporter Robert Pear, takes up about 750 words at the top of page A2 in today’s Globe — and 1,170 words on page A18 of the Times.

For many years — even for the first decade or so of Times Co. ownership — the Globe never ran Times articles. Instead, the Globe supplemented its own coverage with journalism from wire services and from newspapers such as The Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times.

Somewhere along the line, though, someone at the Mother Ship decided the Times Co. could save money by running Times articles in the Globe. It’s hard to argue with the math — no matter how they did the accounting, it was essentially free content.

I don’t know how many people subscribe to both the Times and the Globe. The number may be very small. But those double subscribers tend to be journalists, community leaders and opinion makers — the very people Henry needs to court as he embarks on his new career as a newspaper owner.

Dumping the Times would serve as an emphatic statement that he intends to chart a new, independent course for the Globe.

At the Times, quoting the voices in their heads

What is the point of this pointless speculation in an otherwise straightforward piece on U.S. raids in Libya and Somalia, New York Times?

With President Obama locked in a standoff with Congressional Republicans and his leadership criticized for a policy reversal in Syria, the raids could fuel accusations among his critics that the administration was eager for a showy foreign policy victory.

No sourcing. But if anyone in the Republican Party were to go there, it might be House Speaker John Boehner. Well, here’s Boehner on ABC’s “This Week”:

I’m very confident that both of these efforts were successful. I’m going to congratulate all of those in the U.S. intelligence operations, our troops, FBI, all those who were involved.

Listen, the threat of al Qaeda and their affiliates remains. And America has continued to be vigilant. And this is a great example of our dedicated forces on the security side, intelligence side, and our military and their capability to track these people down.

What was the Times thinking? Or to put it another way: Why weren’t they thinking?

Hold the uplift, and make that shower extra hot

Earlier this month my wife and I were watching the news when Patrick Leahy came on to talk about something or other — I don’t remember what.

Earlier this month my wife and I were watching the news when Patrick Leahy came on to talk about something or other — I don’t remember what.

Leahy, 73, has been a Democratic senator from Vermont for nearly four decades. Normally that stirs up feelings that, you know, maybe it’s time for the old man to go back to the dairy farm and watch his grandchildren milk the cows.

But I had been reading Mark Leibovich’s “This Town.” And so I felt a tiny measure of admiration for Leahy stirring up inside me. He hadn’t cashed in. (His net worth — somewhere between $49,000 and $210,000 — makes him among the poorer members of the Senate, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.) He hasn’t become a lobbyist. He apparently intends to die with his boots on.

That amounts to honor of a sort in the vomitrocious Washington that Leibovich describes in revolting detail — a town of sellouts and suckups (“Suckup City” was one of his working titles), a place where the nation’s business isn’t just subordinate to the culture of money and access, but is, at best, an afterthought.

If you plan to review a book, you shouldn’t “read” the audio version. I have no notes, no dog-eared pages to refer to. So consider this not a review so much as a few disjointed impressions of “This Town,” subtitled “Two Parties and a Funeral — Plus, Plenty of Valet Parking! — in America’s Gilded Capital.”

Mark is an old acquaintance. He and I worked together for a couple of years at The Boston Phoenix in the early 1990s before he moved on to the San Jose Mercury News, The Washington Post and, finally, The New York Times. (Other former Phoenicians who’ve reviewed “This Town”: Peter Kadzis in The Providence Phoenix and Marjorie Arons-Barron for her blog.)

There are many good things I could say about Mark and “This Town,” but I’ll start with this: I have never known anyone who worked harder to improve. It was not unusual for me to leave the Phoenix in the evening while Mark was working on an article — and to come back the next morning to find him still at it. The result of all that labor is a finely honed sense of craft that most of us can only aspire to.

As virtually every reviewer has pointed out, “This Town” begins with a masterful description of the funeral service for “Meet the Press” impresario Tim Russert, an ostensibly mournful occasion that provided the media and political classes in Washington with an opportunity to carry out the real business of their community: talking about themselves and checking their place in the pecking order.

There are so many loathsome characters in “This Town” that you’d need an index to keep track of them all. And Leibovich puckishly refused to provide one, though The Washington Post published an unofficial index here. For my money, though, the lowest of the low are former senator Evan Bayh and former congressman Dick Gephardt — Democrats who left office but stayed in Washington to become highly paid lobbyists. Bayh, with his unctuously insincere laments over how broken Washington had become, and Gephardt, who quickly sold out every pro-labor position he had ever held, rise above (or descend below) a common streetwalker like Chris Dodd, who flirted not very convincingly with becoming an entrepreneur before entering the warm embrace of the film industry.

Also: If you have never heard of Tammy Haddad, Leibovich will remove your innocence. You will be sadder but wiser.

Because Mark is such a fine writer, he operates with a scalpel; those of us who have only a baseball bat to work with can only stand back in awe at the way he carves up his subjects. Still, I found myself occasionally wishing he’d grab his bat and do to some of these scum-sucking leeches what David Ortiz did to that dugout phone in Baltimore.

Mike Allen of Politico, for instance, comes off as an oddly sympathetic character despite the damage he and his news organization have done to democracy with their focus on politics as a sport and their elevation of trivia and gossip. (To be sure, Leibovich describes that damage in great detail.) I could be wrong, but it seems to me that that Mark was tougher on Allen in a profile for the Times Magazine a few years ago.

Thus I was immensely pleased to hear Mark (or, rather, narrator Joe Barrett) administer an old-fashioned thrashing to Sidney Blumenthal. It seems that Blumenthal, yet another former Phoenix reporter, had lodged a bogus plagiarism complaint against Mark because Blumenthal had written a play several decades ago called “This Town,” which, inconveniently for Sid Vicious, no one had ever heard of. More, please.

I also found myself wondering what Leibovich makes of the Tea Party and the Republican Party’s ever-rightward drift into crazyland. The Washington of “This Town” is rather familiar, if rarely so-well described. The corruption is all-pervasive and bipartisan, defined by the unlikely (but not really) partnership of the despicable Republican operative Haley Barbour and the equally despicable Democratic fundraiser Terry McAuliffe.

No doubt such relationships remain an important part of Washington. But it seems to me that people like Rand Paul, Ted Cruz and their ilk — for instance, the crazies now talking about impeaching President Obama — don’t really fit into that world. And, increasingly, they’re calling the shots, making the sort of Old Guard Republicans Leibovich writes about (Republicans like John Boehner and Mitch McConnell, for instance) all but irrelevant.

But that’s a quibble, and it would have shifted Mark away from what he does best: writing finely honed character studies of people who have very little character. “This Town” is an excellent book that says much about why we hate Washington — and why we’re right to keep on doing so. Hold the uplift. And make sure the shower you’ll need after reading it is extra hot.

What happened at The Guardian could happen here

This commentary was first published at The Huffington Post.

As you have no doubt already heard, Alan Rusbridger, editor of The Guardian, wrote on Monday that British security agents recently visited the newspaper’s headquarters and insisted that hard drives containing leaked documents from Edward Snowden be smashed and destroyed in their presence. The incident, Rusbridger said, took place after a “very senior government official” demanded that the materials either be returned or disposed of.

Rusbridger’s report followed the nearly nine-hour detention of Glenn Greenwald’s partner, David Miranda, at London’s Heathrow Airport. Greenwald has written the bulk of The Guardian’s articles about the Snowden documents, and Miranda had been visiting filmmaker Laura Poitras, who has worked extensively with Snowden and Greenwald, in Berlin.

We are already being told that such thuggery couldn’t happen in the United States because of our constitutional protections for freedom of the press. For instance, Ryan Chittum of the Columbia Journalism Review writes, “Prior restraint is the nuclear option in government relations with the press and unfortunately, the British don’t have a First Amendment.”

But in fact, there is nothing to stop the U.S. government from censoring the media with regard to revelations such as those contained in the Snowden files — nothing, that is, except longstanding tradition. And respect for that tradition is melting away, as I argued recently in this space.

The case for censorship, ironically, was made in a U.S. Supreme Court decision that severely limited the circumstances under which the government could censor. The decision, Near v. Minnesota (1931), was a great victory for the press, as the ruling held that Jay Near could not be prohibited from resuming publication of his scandal sheet, which had been shut down by state authorities (of course, he could be sued for libel after the fact).

What’s relevant here is how Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes described the limited circumstances under which the government could engage in prior restraint:

No one would question but that a government might prevent actual obstruction to its recruiting service or the publication of the sailing dates of transports or the number and location of troops. On similar grounds, the primary requirements of decency may be enforced against obscene publications. The security of the community life may be protected against incitements to acts of violence and the overthrow by force of orderly government.

The text I’ve bolded means that the government may, in fact, engage in censorship if by so doing it would prevent a breach of national security so grave that it could be likened to the examples cited by Hughes. That’s what the Nixon administration relied on in seeking to stop The New York Times and The Washington Post from publishing the Pentagon Papers in 1971.

The Supreme Court, in allowing publication of the Pentagon Papers to resume (New York Times Co. v. United States), wrestled extensively with Near v. Minnesota, and ultimately decided that revealing the government’s secret history of the Vietnam War did not amount to the sort of immediate, serious breach of national security that Hughes envisioned.

But who knows what the court would say if the Obama administration took similar action against The Washington Post, which has published several important reports based on the Snowden documents — including last week’s Barton Gellman bombshell that the National Security Agency had violated privacy protections thousands of times?

Unlike the Pentagon Papers, the Snowden documents pertain to ongoing operations, which cuts in favor of censorship. Cutting against it, of course, is that there’s a strong public-interest case to be made in favor of publication, given the long-overdue national debate that Snowden’s revelations have ignited.

The bottom line, though, is that there is no constitutional ban that would prevent the White House from seeking to stop publication of the Snowden documents — even if U.S. officials are unlike to engage in the sort of theatrics that reportedly took place in The Guardian’s basement.

(Disclosure: I wrote a weekly online column for The Guardian from 2007 to 2011.)

Branzburg v. Hayes v. The New York Times

You may not like a federal appeals court’s decision that New York Times reporter James Risen must testify in a CIA leak case. I don’t. But it’s Branzburg v. Hayes, straight up. It’s unimaginable that this would have gone the other way.

And keep in mind that even if we had a federal shield law, there would almost certainly be a national-security exception wide enough to drive a truckload of subpoenas through.

Some thoughts on that Rolling Stone cover (II)

Front page of the Sunday New York Times, May 5. Same picture of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, page one, above the fold. Here is the story. Does anyone really want to argue that what the Times did is somehow different from what Rolling Stone did?

Also, a very smart commentary in The New Yorker by Ian Crouch.