I listened to this mind-boggling story from “This American Life” on patent madness as I was driving home from Connecticut earlier today. Our out-of-control patent system is destroying innovation and harming the economy. Be prepared to be horrified.

Category: Technology

Commenting on Media Nation

Harvey Silverglate’s provocative post on the Aaron Swartz case has brought in a number of new commenters. If you don’t see your comment posted, it’s because you did not use your full name, first and last. Please see this and feel free to resubmit.

The Swartz suicide and the sick culture of the Justice Dept.

Republished by permission of Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly, where this article first appeared. Thanks to my friend Harvey for making this available to readers of Media Nation.

Republished by permission of Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly, where this article first appeared. Thanks to my friend Harvey for making this available to readers of Media Nation.

By Harvey A. Silverglate

Some lawyers are joking when they refer to the Moakley Courthouse as “the House of Pain.” I’m not.

The ill-considered prosecution leading to the suicide of computer prodigy Aaron Swartz is the most recent in a long line of abusive prosecutions coming out of the U.S. attorney’s office in Boston, representing a disastrous culture shift. It sadly reflects what’s happened to the federal criminal courts, not only in Massachusetts but across the country.

It’s difficult for lawyers to step back and view the larger picture of the unflattering system from which we derive our status and our living. But we have an ethical obligation to criticize the legal system when warranted.

Who else, after all, knows as much about where the proverbial bodies are buried and is in as good a position to tell truth to power as members of the independent bar?

Yet the palpable injustices flowing regularly out of the federal criminal courts have by and large escaped the critical scrutiny of the lawyers who are in the best position to say something. And judges tend not to recognize what to outsiders are serious flaws, because the system touts itself as the best and fairest in the world.

Since the mid-1980s, a proliferation of vague and overlapping federal criminal statutes has given federal prosecutors the ability to indict, and convict, virtually anyone unfortunate enough to come within their sights. And sentencing guidelines confer yet additional power on prosecutors, who have the discretion to pick and choose from statutes covering the same behavior.

This dangerous state of affairs has resulted in countless miscarriages of justice, many of which aren’t recognized as such until long after unfairly incarcerated defendants have served “boxcar-length” sentences.

Aaron Swartz was a victim of this system run amok. He was indicted under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, a notoriously broad statute enacted by Congress seemingly to criminalize any use of a computer to do something that could be deemed bad.

As Harvard Law School Internet scholar Lawrence Lessig has written for The Atlantic: “For 25 years, the CFAA has given federal prosecutors almost unbridled discretion to bully practically anyone using a computer network in ways the government doesn’t like.”

Swartz believed that information on the Internet should be free to the extent possible. He entered the site operated by JSTOR, a repository of millions of pages of academic articles available for sale, and downloaded a huge cache. He did not sell any, and while it remains unclear exactly how or even if he intended to make his “information should be free” point, no one who knew Swartz, not even the government, thought he was in it to make money.

Therefore, JSTOR insisted that criminal charges not be brought.

U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz obscured that point when announcing the indictment. “Stealing is stealing, whether you use a computer command or a crowbar, whether you take documents, data or dollars, and whether its to feed your children or for buying a new car” she said, failing to recognize the most basic fact: that Swartz neither deprived the owners of the articles of their property nor made a penny from his caper. Continue reading “The Swartz suicide and the sick culture of the Justice Dept.”

How empty space led to experimentation at the Globe

The New York Times has a terrific story today about how the downsized Boston Globe — a sister paper — has turned over a chunk of unused space to entrepreneurs, its online radio station, RadioBDC, and even a pilot for a television series.

As Times reporter Christine Haughney observes, the experimental venture by Globe publisher Christopher Mayer has already paid off in the form of a partnership with Michael Morisy, the co-founder of the public-records website MuckRock.

Dominating the space is the Idea Lab, where a small group of smart young people try out new ideas, such as different approaches to tracking Globe stories on social media and a wall-size group of screens that plots Instagram photos on a map of Boston. The latter ended up playing a role in the Globe’s recent interactive series on life in the Bowdoin-Geneva neighborhood of Dorchester, “68 Blocks: Life, Death, Hope.”

I’ve brought several groups of students to tour the Idea Lab. For anyone interested in the future of journalism, it’s one of the most interesting places you can visit.

Photo © 2012 by Megan Lieberman and used by permission.

Sununu blasts MIT and Carmen Ortiz in Swartz case

It’s interesting that even a conservative like John E. Sununu is disgusted with the actions of MIT and U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz regarding their investigation of the late Internet democracy activist Aaron Swartz.

Sununu, an MIT graduate with some serious basketball moves, writes in The Boston Globe that Swartz was charged criminally for behavior that in an earlier time might have been considered no more serious than any one of a number of pranks for which the university is known. The whole thing, he says, should have been handled in house:

Whereas the institute once would have taken pains to find an appropriate and internal resolution to violations of regulations — and even laws — within its campus, it chose to defer to others. That reaction isn’t unique to MIT, but rather a reflection of gradual changes in accepted cultural and government behavior over the past 20 years. Today, regulators and prosecutors regularly use their power to impose agreements, plea bargains, and consent decrees with little judicial review. They threaten the maximum penalty allowable — regardless of whether a rational mind would consider it fitting for the infraction — in order to gain an outcome that enhances their stature or pleases their political base.

Meanwhile, Noam Cohen of The New York Times takes a detailed look at how MIT caught Swartz, who downloaded nearly 5 million academic articles from the JSTOR subscription service without authorization.

The Globe turns up the heat on Carmen Ortiz

Given The Boston Globe’s past favorable coverage of U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz, I’m heartened to see how aggressively the paper is covering her conduct in the investigation of the late Internet activist Aaron Swartz.

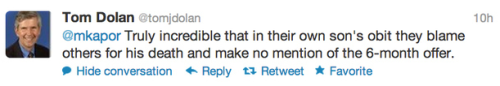

Today the Globe fronts a story by Shelley Murphy about some repulsive tweets posted by Ortiz’s husband, IBM executive Thomas Dolan, in which he defended his wife and lashed out against Swartz’s grieving parents. Dolan’s Twitter feed has since disappeared, but BuzzFeed posted what I can only hope is the worst of them Tuesday.

Today the Globe fronts a story by Shelley Murphy about some repulsive tweets posted by Ortiz’s husband, IBM executive Thomas Dolan, in which he defended his wife and lashed out against Swartz’s grieving parents. Dolan’s Twitter feed has since disappeared, but BuzzFeed posted what I can only hope is the worst of them Tuesday.

Murphy’s story follows an angry piece by Globe columnist Kevin Cullen on Tuesday. Cullen wrote:

The argument about whether prosecutors should have been insisting that Swartz, who had written openly and movingly about his struggle with depression, serve at least six months in prison is not an academic question. It is a question about proportionality and humanity, and on both fronts the office of US Attorney Carmen Ortiz and the prosecutors who handled this case, Steve Heymann and Scott Garland, failed miserably.

For too long Ortiz has led a charmed existence, using and abusing the power of her office in order to burnish her law-and-order credentials. In 2011 The Boston Globe Magazine went so far as to name her its “Bostonian of the Year.”

Ortiz is not to blame for the suicide of a young man who had long struggled with depression. Nevertheless, her insistence that he serve prison time was absurd given the nature of his offense. Now we’ve lost a brilliant, creative thinker whose greatest contributions were yet to come.

Correction: Updated to fix Thomas Dolan’s name.

Aaron Swartz, Carmen Ortiz and the meaning of justice

An earlier version of this commentary was published on Sunday at The Huffington Post.

The suicide of Internet activist Aaron Swartz has prompted a wave of revulsion directed at U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz, who was seeking to put him in prison for 35 years on charges that he illegally downloaded millions of academic articles.

Swartz, 26, who helped develop the RSS standard and was a co-founder of Reddit, was “driven to the edge by what a decent society would only call bullying,” wrote his friend and lawyer Lawrence Lessig. “I get wrong,” Lessig added. “But I also get proportionality. And if you don’t get both, you don’t deserve to have the power of the United States government behind you.”

By Monday morning, more than 11,000 people had signed an online petition asking President Obama to remove Ortiz. Swartz’s family released a statement that said in part: “Aaron’s death is not simply a personal tragedy. It is the product of a criminal justice system rife with intimidation and prosecutorial overreach.”

Ortiz’s vindictiveness toward Swartz may have seemed shocking given that even the victim of Swartz’s alleged offense — the academic publisher JSTOR — did not wish to press charges. But it was no surprise to those of us who have been observing Ortiz’s official conduct as the top federal prosecutor in Boston.

Last July I singled out Ortiz as the lead villain in the 2012 Muzzle Awards, an annual feature I’ve been writing for the Phoenix newspapers of Boston, Providence and Portland since 1998. The reason: her prosecution of Tarek Mehanna, a Boston-area pharmacist who had acted as a propagandist for Al Qaeda.

Mehanna was sentenced to prison for 17 years — not because of what he did, but because of what he said, wrote and translated. Though Mehanna had once unsuccessfully sought training at a jihadi terrorist camp in Yemen, the government’s case was based almost entirely on activities that were, or should have been, protected by the First Amendment.

Make no mistake: Mehanna’s propaganda was “brutal, disgusting and unambiguously supportive of Islamic insurgencies in Iraq, Afghanistan and Somalia,” Yale political scientist Andrew March wrote in The New York Times. But as March, the ACLU and others pointed out in defense of Mehanna, the more loathsome the speech, the more it deserves protection under the Constitution.

In addition to the prosecution of Tarek Mehanna and the persecution of Aaron Swartz, there is the matter of Sal DiMasi, a former speaker of the Massachusetts House who is now serving time in federal prison on political corruption charges brought by Ortiz.

Last June DiMasi revealed he had advanced tongue cancer — and he accused federal prison authorities of ignoring his pleas for medical care while he was shuttled back and forth to Boston so that he could be questioned about a patronage scandal Ortiz’s office was investigating. It would be a stretch to connect Ortiz directly with DiMasi’s health woes. She is, nevertheless, a key player in a system that could transform DiMasi’s prison sentence into a death sentence.

Notwithstanding the anger that has been unleashed at Ortiz following Aaron Swartz’s death, she should not be regarded as an anomaly. As the noted civil-liberties lawyer Harvey Silverglate pointed out in his 2009 book, “Three Felonies a Day: How the Feds Target the Innocent,” federal prosecutors have been given vague, broad powers that have led to outrages against justice across the country.

“Wrongful prosecution of innocent conduct that is twisted into a felony charge has wrecked many an innocent life and career,” wrote Silverglate, a friend and occasional collaborator. “Whole families have been devastated, as have myriad relationships and entire companies.”

Ortiz may now find that her willingness to use those vast powers against Swartz could have a harmful effect on her future.

As a Latina and as a tough law-and-order Democrat, she has been seen as a hot political property in Massachusetts. In 2011 The Boston Globe Magazine named her its “Bostonian of the Year.” She recently told the Boston Herald she was not interested in running for either the U.S. Senate or governor. But that doesn’t mean she couldn’t be persuaded. Now, though, she may be regarded as damaged goods.

Those who are mourning the death of Aaron Swartz should keep in mind that he had long struggled with depression. Blaming his suicide on Carmen Ortiz is unfair.

Nevertheless, the case she was pursuing against Swartz was wildly disproportionate, and illustrated much that is wrong with our system of justice. Nothing good can come from his death. But at the very least it should prompt consideration of why such brutality has become a routine part of the American system of justice.

Update: MIT, where Swartz allegedly downloaded the JSTOR articles, has announced an internal investigation, reports Evan Allen of The Boston Globe. Lauren Landry of BostInno has statements from MIT president Rafael Reif and from JSTOR.

Photo (cc) by Daniel J. Sieradski via Wikimedia Commons and published here under a Creative Commons license. Some rights reserved.

Technical difficulties ahead

I’m making some changes to Media Nation that may result in the site’s being down off and on during the next few days. You’ll still be able to access it at dankennedy.wordpress.com, but don’t bother bookmarking it — that’s just a temporary solution.

Naming names

I’ve seen an uptick in anonymous, pseudonymous and first-name-only comments recently. Some of them are really good, but I won’t post without a real name, first and last — clearly spelled out when you try to post. Here is the full Media Nation comments policy along with some of my reasons for implementing it.

In some cases, it may just be a matter of how you registered with WordPress. (Note: Registration is not necessary.) If you think that’s you, please read this.

A new look for Media Nation?

I’m trying a new WordPress theme. Thoughts? (Update: Yuck. Back to the old theme.)