Previously published at WGBHNews.org.

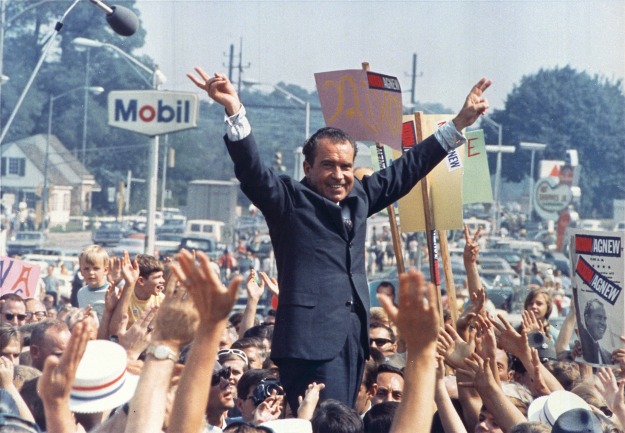

More than 40 years after he resigned as president, Richard Nixon remains the lodestar for political skullduggery. And so it was when Donald Trump threatened to retaliate against Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos in response to news that the Post is siccing 20 reporters on Trump to look into every aspect of his life and career.

Details about the Post’s Trump project, which will include a book, emanated from the lips of Post associate editor Bob Woodward, a twist that made it all the more cosmically significant. For it was Woodward, along with fellow Post reporter Carl Bernstein, who helped end Nixon’s presidency in 1974—but not before the Post had endured some fearsome attacks from the Nixon White House that threatened not just the newspaper but the First Amendment’s guarantee of a free press.

As you may have heard, Bezos’s day job is running Amazon, the online retailing behemoth that he founded. Trump, the presumptive Republican presidential nominee, told Fox News host Sean Hannity that Amazon has “a huge antitrust problem” and “is getting away with murder, tax-wise.” He added that Bezos is “using the Washington Post for power so that the politicians in Washington don’t tax Amazon like they should be taxed.”

Never mind that there is zero evidence for Trump’s accusation. His implied threat was utterly Nixonian in its stark assertion that he’d use the powers of government to harm Bezos in retaliation for journalism that he doesn’t like.

The roots of Nixon’s hatred for the Post extend back to the 1950s. David Halberstam, in his book The Powers That Be, wrote that it began over the cartoonist Herbert Block. Herblock, as he was known, regularly portrayed Nixon as a malign figure with a perpetual five-o’clock shadow, and his work was syndicated in hundreds of papers around the country. According to Halberstam, Herblock’s cartoons “became part of Nixon’s permanent dossier, reflecting all the public doubts and questions about him.”

It wasn’t until the 1970s, though, that Nixon attempted to translate that anger into action. In 1971, the Post joined the New York Times in publishing the Pentagon Papers, the government’s secret history of the Vietnam War, which showed that American officials had continued the fighting out of political cowardice for years after concluding that it was unwinnable.

According to then-publisher Katharine Graham in her autobiography, Personal History, the Nixon White House issued “a not very veiled threat” that the paper might face a criminal prosecution if it didn’t turn over its copy of the Pentagon Papers to the government. At the time, the Post was on the verge of becoming a publicly traded company, and it would have been devastating to the paper’s plan to raise money from the stock market if it had been convicted of a crime. And as my fellow WGBH News contributor Harvey Silverglate wrote for the Phoenix newspapers some years back, the Nixon administration actually considered prosecuting the Times and the Post even after the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the papers’ right to publish.

Woodward and Bernstein’s reporting on the Watergate scandal brought about perhaps the most infamous threat ever made against a newspaper. When Bernstein asked Nixon henchman John Mitchell to comment on a particularly damaging story, Mitchell responded: “Katie Graham’s gonna get her tit caught in a big fat wringer if that’s published.” More substantively, Nixon allies arose from the swamp to challenge the Post’s ownership of two television stations in Florida—challenges that faded away once Nixon had resigned from office.

“Henry Kissinger told me he felt that Nixon had always hated the Post,” Graham wrote, quoting Kissinger as saying of Nixon: “He was convinced that the Post had it in for him.” As Graham described it, the Post’s reporting on Nixon during the Watergate years became an existential crisis. If the paper hadn’t been able to prove Nixon’s involvement in the Watergate break-in and related crimes and thus force Nixon from office, the Post itself would have been destroyed.

Although the showdown between Nixon and the Post is the most dramatic example of the government’s attempting to destroy its journalistic adversaries, it is not the only one.

In the early days of World War II, after Colonel Robert McCormick’s Chicago Tribune reported that the United States may have cracked Japanese codes, President Franklin Roosevelt considered trying McCormick for treason, which could have resulted in the death penalty. FDR was talked out of it only because his advisers convinced him that such a drastic measure would only serve to alert the Japanese.

More recently, President George W. Bush’s Justice Department raised the possibility that the New York Times and the Washington Post could be prosecuted under espionage laws for reporting on a National Security Agency surveillance program (the Times) and on the rendition of terrorism suspects to countries that engage in torture (the Post).

And, of course, there is President Barack Obama’s relentless pursuit of government officials who leak information to the media—a pursuit that has ensnared a number of journalists, including James Risen of the New York Times. Risen fought the government for seven years so that he wouldn’t have to reveal the identity of the sources who had told him how the CIA had sought to wreak havoc with Iran’s nuclear program. Last year Risen called the Obama administration “the greatest enemy of press freedom in a generation.”

But note that Roosevelt’s, Bush’s, and Obama’s attacks on the press were grounded in legitimate concerns about national security, misguided though Bush may have been and Obama may be. (It’s hard to argue with FDR’s fury at McCormick, whose actions would not be protected by even the most expansive reading of the First Amendment.)

By contrast, Trump, like Nixon during Watergate, would go after the press purely for personal reasons—not by denouncing the media (or, rather, not just by denouncing the media) but by abusing his powers as president. Bring negative information to light about Nixon and you might lose your television stations. Report harshly on Trump and your tax status might be threatened—and you may even face an antitrust suit.

This is the way authoritarians reinforce their power—through fear and intimidation, the rule of law be damned. Despite all the benefit he has received in the form of free media, Trump hates the press. He has threatened to rewrite the libel laws, and now he’s threatened the owner of one of our great newspapers.

Trump is a menace on so many levels that it’s hard to know where to begin. But we can add this: Like Nixon, he is a threat to the First Amendment, our most important tool in holding the government accountable to the governed.