Previously published at WGBHNews.org.

There are two elephants in the room that are threatening to destroy local news.

One, technological disruption, is widely understood: the internet has undermined the value of advertising and driven it to Craigslist, Facebook and Google, thus eliminating most of the revenues that used to pay for journalism.

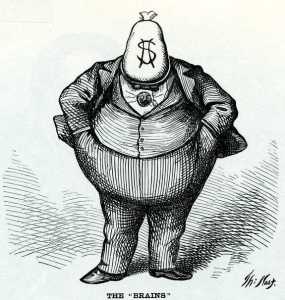

But the other, corporate greed, is too often regarded as an effect rather than as a cause. The standard argument is that chain owners moved in to suck the last few drops of blood out of local newspapers because no one else wanted them. In fact, the opposite is the case. Ownership by hedge funds and publicly traded corporations has squeezed newspapers that might otherwise be holding their own and deprived them of the runway they need to invest in the future.

The last several weeks have been brutal for local newspapers. GateHouse Media and Gannett merged (the new company is known simply as Gannett), a union of two bottom-feeding chains that are reported to be considering at least another $400 million in cuts. MediaNews Group, owned by the hedge fund Alden Global Capital, acquired a 32% share of the Tribune newspapers. McClatchy may be moving toward bankruptcy.

And yet, here and there, independent community news projects are thriving. Free of the debt that must be taken on to build a chain and of the need to ship revenues to their corporate overlords, the indies — both for-profit and nonprofit — are meeting the information needs of their communities.

The narrative about the death of local journalism is an easy one to grasp, because the tale of technological disruption used to explain it has quite a bit of truth to it, as Lehigh University journalism professor Jeremy Littau wrote in a widely quoted Twitter thread over the weekend. The narrative of the ongoing vitality of local journalism doesn’t get heard often enough because it’s harder to wrap your arms around. It’s happening here and there, with different approaches and without a one-size-fits-all solution.

As such, examples are necessarily anecdotal — and you know the saying that anecdotes aren’t data. Still, good things are happening at the grassroots. For instance:

• The small daily newspaper where I worked for my first 10 years out of college, The Daily Times Chronicle of Woburn, is still owned by the founding Haggerty family and still providing decent coverage of the communities it serves. The paper is smaller than it used to be, but it’s doing far better work than a typical chain-owned paper.

• Several months ago I had an opportunity to attend the fall conference of the New York Press Association, which comprises upstate independent publishers. Those folks told me that though business was more challenging than ever, their papers were doing reasonably well.

• New Haven, Connecticut, may enjoy the best coverage of any medium-sized city in the country. Why? One veteran journalist, Paul Bass, had the vision to create the nonprofit, online-only New Haven Independent, supported by grants and donations, and still thriving 14 years after its founding. (The Independent is the main subject of my 2013 book, “The Wired City.”)

• For-profit digital news sites are doing well in some places, too. Among them: The Batavian, in Western New York, also profiled in “The Wired City.” Overall, there are enough for-profit and nonprofit sites that they have their own trade organization, LION (Local Independent Online News) Publishers. No, their numbers are too small to offset the overall decline. But the opportunity is out there for entrepreneurial-minded journalists. The chains, sadly, are creating more opportunities every day.

• Among the regions I reported on in my 2018 book, “The Return of the Moguls,” was Burlington, Vermont, whose daily, the Burlington Free Press, had been decimated by Gannett. What happened? An excellent, for-profit alternative weekly, Seven Days, bolstered its online news coverage. Two nonprofit news organizations, Vermont Public Radio and VT Digger, beefed up their local coverage as well.

• In Western Massachusetts, the once-great Berkshire Eagle is being rebuilt by local owners who bought it from MediaNews Group several years ago. That could provide a roadmap for other communities — at some point, chain owners will no longer be able to keep cutting their way to profits and will presumably be looking for a way out.

• Regional newspapers are experimenting with new forms of ownership. The Salt Lake Tribune recently won IRS approval to become a nonprofit organization. The Philadelphia Inquirer, though still a for-profit, is now owned by the nonprofit Lenfest Foundation. Neither of these moves guarantees salvation. But it has bought them time to shift to a new business model built less on advertising and more on support from their readers.

• Speaking of which: It’s been nearly a year since The Boston Globe announced it had achieved profitability despite continuing to employ a newsroom far larger than any chain owner would tolerate.

No, there is little hope of returning to the old days. Newspapers will never be as richly staffed as they were before the early 2000s, when the internet began to take a toll on revenues. Papers will continue to die. Nonprofits will have to become an increasingly important part of the mix.

Washington Post media columnist Margaret Sullivan wrote the other day that “the recent news about the news could hardly be worse. What was terribly worrisome has tumbled into disaster.”

She’s right. But in all too many instances, local news isn’t dying — it’s being murdered. The solution, if there is to be one, has to start with getting the corporate chains out of the way and paving a path for a new generation of independent publishers.

Talk about this post on Facebook.