On the East Coast, The Washington Post is in the midst of a revival that could return the storied newspaper to its former status as a serious competitor to The New York Times for national and international news. On the West Coast, the Orange County Register is rapidly sinking into the pit from which it had only recently crawled.

On the East Coast, The Washington Post is in the midst of a revival that could return the storied newspaper to its former status as a serious competitor to The New York Times for national and international news. On the West Coast, the Orange County Register is rapidly sinking into the pit from which it had only recently crawled.

The two contrasting stories are told by the Columbia Journalism Review’s Michael Meyer, who writes about the Post in the early months of the Jeff Bezos era, and Gustavo Arellano of OC Weekly, who’s been all over Aaron Kushner since his arrival as the Register’s principal owner in 2012.

First the Post, which has been the subject of considerable fascination since Amazon founder Bezos announced last August (just a few days after John Henry said he would buy The Boston Globe) that he would purchase the paper from the Graham family for $250 million.

Bezos’ vision, as best as Meyer could discern (Bezos, as is his wont, did not give him an interview), is to leave the journalists alone and work on ways to expand the Post’s digital audience across a variety of platforms. Meyer describes a meeting that Bezos held in Seattle with executive editor Marty Baron and other top managers:

Baron says he came away from the weekend in Seattle with a clear sense of what the Post’s mission would be in the coming year: It had to have “a more expansive national vision” in order to achieve the ultimate goal of substantially growing its digital audience. Baron brought this directive back to the newsroom, and the editors set about building a plan for 2014, a year managing editor Kevin Merida dubbed “the year of ambition.” At one point in the budgeting process, Bezos even admonished the leadership for not thinking big enough. “I think that we had been in the mode of sort of watching our pennies,” Baron told me. “We were just being more cautious at the beginning so he came back with an indication that we should be more ambitious.”

Among the more perplexing moves (to me at least) that the Post has made under Bezos has been to cut deals with more than 100 daily papers across the country so that paid subscribers to those papers would receive free digital access to the Post as well. Locally, the papers include the Portland Press Herald as well as Digital First Media’s papers, such as The Sun of Lowell, The Berkshire Eagle and the New Haven Register.

Journalistically, it’s a good deal for subscribers, since they get free access to a high-quality national news source. But no money changes hands. So how is it any better for the Post than simply offering a free advertiser-supported website, as it did until instituting a metered paywall last year? Meyer tells me by email that “the reason they are doing this is for customer data. A logged in, regular user is a lot more data rich than someone who just happens across your site from time to time.” He adds:

Data is the key difference between this program and just having a free website. And another key difference to my mind is psychological. The readers of partner newspapers feel like they’re being given something that would otherwise not be free. This adds value in terms of how they view their subscriptions to their home newspapers. And also adds value in terms of how they view the Post’s content. My guess is they will use the service more as a result.

And as Meyer writes in his story, “Anyone interested in seeing how consumer data might be used in the hands of Jeff Bezos can go to Amazon.com and watch the company’s algorithms try to predict their desires.”

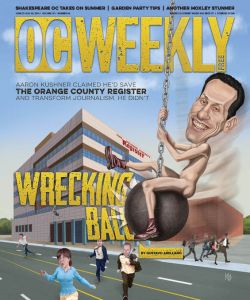

The story Gustavo Arellano tells about Aaron Kushner and the Orange County Register has become well-known in recent weeks, in large measure because of Arellano’s own coverage in the OC Weekly. Kushner has spent 2014 rapidly dismantling what he spent 2012 and 2013 building up.

The story Gustavo Arellano tells about Aaron Kushner and the Orange County Register has become well-known in recent weeks, in large measure because of Arellano’s own coverage in the OC Weekly. Kushner has spent 2014 rapidly dismantling what he spent 2012 and 2013 building up.

As I wrote recently in The Huffington Post, it makes no sense to invest in growth unless you have enough money to wait and see how it plays out, which is clearly the case with Bezos at the Post and Henry at the Globe — and which now is clearly not the case with Kushner and the Register.

The Orange County meltdown was also the subject of an unusually nasty blog post earlier this month by Clay Shirky, who criticized Ryan Chittum of the CJR and Ken Doctor of Newsonomics and the Nieman Journalism Lab for overlooking the weaknesses in Kushner’s expansion. (Chittum and Doctor wrote detailed, thoughtful responses, and I’ve linked to both of them in the comments of a piece I wrote about the kerfuffle for WGBHNews.org.)

Arellano has gotten hold of some internal documents that make it clear that Kushner’s expansionary dreams were doomed from the start. He also paints a picture of a poisoned newsroom and offers lots of anonymous quotes to back it up.

“I wouldn’t say I got hoodwinked,” he quotes one former staff member as saying, “but it’s just another lesson of life: If it’s too good to be true, it is.”

I recently criticized Arellano for his overreliance on anonymous quotes, although I freely concede that I used them regularly when I was covering the media for The Boston Phoenix in the 1990s and the early ’00s. This time, he includes a clear explanation of why almost none of his sources would go on the record: fear of “reprisal or the endangerment of their buyout, which included a nondisclosure clause.” Given that, I think the story is stronger with the quotes than without.

Arellano writes:

In retrospect, it seems obvious Kushner set himself up for failure, like a Jenga tower depending on every precariously placed block. He installed himself as publisher despite having no previous newspaper experience. A hard paywall — his most controversial move — was erected to force readers to buy the print edition in an era when online content is king. To justify that, Kushner plunged into a hiring binge that saw the Register sign up hundreds of employees even though it didn’t have the revenue to pay them. To fund his vision, the sales department was tasked with selling all those points despite an industry-wide decline in print advertising during the past decade.

It’s a sad, ugly moment for a tale that began so optimistically. As for whether this will prove to be the end of the story — well, it sure looks that way, although Kushner insists he’s merely slowed down. After two years of hiring binges and layoffs, the launch and virtual folding of the Long Beach Register, and the inexplicably odd decision to start a Los Angeles Register to compete with the mighty Times, Kushner is clearly down to his last chance — if that.