Previously published at GBH News.

For the first time in a quarter century, serious efforts are under way to make fundamental changes to the Boston School Committee, whose members have been chosen by the mayor since 1992.

City Councilors Ricardo Arroyo and Julia Mejia have filed a home-rule petition with the state Legislature that would replace the current seven-member appointed body with a 13-member panel, all chosen by the voters. A nonbinding question will be on the ballot in November asking voters whether they want to return to an elected school committee. Mayoral candidate Michelle Wu has proposed a committee that would be partly elected and partly appointed by the mayor. Wu’s opponent, Annissa Essaibi George, has suggested a more modest change, with members being chosen by the mayor and city council.

With the exception of Essaibi George’s plan, the proposals are being touted as a way to restore democracy to the school system, overturning decades of having an appointed elite run public education in the city.

“The whole idea of giving up any vote for anything, [even if] it’s dog catcher, you don’t give it away,” said Jean Maguire, who lost her seat when the elected committee was abolished, in a recent interview with GBH News’ Meg Woolhouse. “That’s power!”

Yet in 1996, when voters defeated a referendum that would have dissolved the then-newly appointed committee and brought back an elected board, one of the main arguments was that putting the mayor firmly in charge of the school system was actually more democratic.

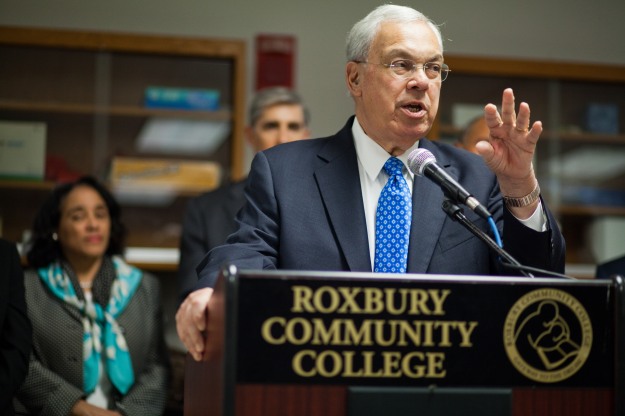

“They elect me,” then-Mayor Tom Menino told me in an interview for The Boston Phoenix at the time. “Hold me accountable for what’s going on in the schools. I’m willing to face the issue head-on.”

The idea that too much democracy can actually work against democracy was articulated in 1909 by the Progressive-era thinker Herbert Croly in his book “The Promise of American Life.” A founder of The New Republic, Croly argued that elections ought to be about big offices and big issues, and that minor elected offices should be eliminated as a way of cutting down on voter confusion and the corrupting influence of “the professional politician.”

“At present, an administration is organized chiefly upon the principle that the executive shall not be permitted to do much good for fear that he will do harm,” Croly wrote. “It ought to be organized on the principle that he shall have full power to do either well or ill, but that if he does do ill, he will have no defense against punishment.”

He added: “A democracy has no interest in making good government complicated, difficult, and costly. It has, on the contrary, every interest in so simplifying its machinery that only decisive decisions and choices are submitted to the voter.”

In 1996, there was another significant reason that voters were reluctant to return to an elected school committee: the legacy of racism. Dominated by white racists like John Kerrigan and Elvira “Pixie” Palladino, the school committee of the 1960s and ’70s resisted desegregation, forcing the intervention of the federal courts. By 1992, when then-Mayor Ray Flynn headed an effort to eliminate the elected committee, matters had improved and the board was more diverse. But memories were still fresh when the fate of the appointed committee appeared on the ballot in 1996.

“We have to remind voters that what they’re returning to is not an unknown alternative. It’s well-known. And its record is disastrous,” the Rev. Ray Hammond said at the time. Or as Ricardo Arroyo’s father, Felix Arroyo, then a member of the appointed school committee, wrote in Otherwise magazine: “Until the voting population reflects the general population of Boston, an elected school committee will not reflect the cultures and rich backgrounds of Boston’s children.” (Otherwise, by the way, was founded and edited by GBH News’ Jim Braude.)

Of course, what was true in 1996 is not necessarily true today. The appointed committee has had a rough year. A white member resigned in October after he was caught mocking the Asian names of several members of the public who were appearing before the panel. Two Latinx members stepped down after it was revealed that they had exchanged texts critical of white parents from West Roxbury. And despite the best efforts of many good people, the school system itself remains troubled.

So maybe it’s time to restore some measure of democracy to the school committee. Wu’s plan is incremental, and Arroyo himself, despite co-sponsoring the home-rule petition, has said he would not object to a hybrid committee of elected and appointed members.

But voters and officials ought to be careful about what they wish for. The next mayor will be a woman of color, which represents substantial progress. Yet all three Black candidates were eliminated in last week’s preliminary election. Boston has come a long way, but it still has a long way to go.

Advocates of an elected school committee might believe that we can’t do any worse. Well, we can, and we have. That doesn’t mean the mayor should be allowed to appoint the members in perpetuity. It does mean that changes need to be made carefully lest some new version of the bad old days is unleashed once again.

There may be more to say later, but I want to offer a few quick thoughts on Mayor Tom Menino’s declaration that he intends to keep Chick-fil-A out of Boston because of the company president’s opposition to same-sex marriage,

There may be more to say later, but I want to offer a few quick thoughts on Mayor Tom Menino’s declaration that he intends to keep Chick-fil-A out of Boston because of the company president’s opposition to same-sex marriage,