Previously published at WGBHNews.org.

Can a news organization help to support itself by opening a café, bar and wedding venue? It’s a good question, but here’s a better one: Can such a gathering place lead to the revival of civic engagement and, thus, to renewed interest in local journalism?

The New York Times last week reported on an interesting experiment taking place at The Big Bend Sentinel of Marfa, Texas. The paper was acquired last year by two former New Yorkers, Maisie Crow and Max Kabat, who quickly found themselves facing the challenge of paying the bills in an era of shrinking ad revenues. Their solution was to renovate a former bar and transform it into a newsroom and café. The revenues, Crow said, would be used to expand the Sentinel’s coverage, explaining that “we wanted to expand the potential.”

But at a time when the decline of civic life is leading to diminishing interest in the day-to-day goings-on that are the staple of local newspapers, bringing journalists and the community together in a common space could help remind residents of why news matters. Indeed, Abbie Perrault, the Sentinel’s managing editor, told the Times that the shared space is “a great way to keep my finger on the pulse and get new leads and find stories.”

The Sentinel is offering a fresh take on an idea that nearly got off the ground a decade ago. That’s when Matt DeRienzo, then the 34-year-old publisher of The Register Citizen in Torrington, Connecticut, was opening up his newsroom to the public with the encouragement of John Paton, an innovative executive who was briefly the toast of the newspaper business.

As The New York Times wrote back then, members of the public could visit The Register Citizen’s Newsroom Café for coffee and muffins and to use the paper’s archives for free. “Matt’s taking his audience and making it a colleague,” Paton was quoted as saying. “A building with open doors, with no walls, is the brick-and-mortar metaphor for how the web works.”

DeRienzo was soon named editor of all of the Journal Register Co. chain’s Connecticut newspapers, including its flagship, the New Haven Register. I interviewed him around that time, and he was brimming with ideas. The company sold off its hulking plant by I-95, and DeRienzo began making plans for an open newsroom on the Yale side of the New Haven Green.

Sadly, it wasn’t to be. Journal Register was merged with another chain, MediaNews Group, and the resulting behemoth was dubbed Digital First Media — an ironic moniker that paid tribute to Paton’s oft-repeated mantra, “digital first,” but that soon proved it was dedicated mainly to squeezing out profits for the benefit of its hedge-fund owner, Alden Global Capital. Paton left. DeRienzo left. And the idea of local journalism reinvented around open newsrooms and public participation faded away. (I told the full story of Digital First’s rise and fall in an earlier WGBH News commentary.)

“It elevated the awareness and reputation of the newspaper and the people who worked in the newsroom,” DeRienzo said of the Torrington experiment in a Facebook discussion last week. “It improved transparency and trust with readers. Our audience grew, and our digital revenue grew.”

Nearly a generation ago, the Harvard sociologist Robert Putnam wrote in his landmark book “Bowling Alone” that newspaper readership correlates strongly with civic engagement. People who vote in local elections, take part in volunteer activities, attend religious services or engage in any number of other activities are also more likely to read the paper. “Newspaper readers,” he wrote, “are machers and schmoozers.”

Which brings us back to The Big Bend Sentinel. The local news crisis has multiple causes, technological change and corporate greed being foremost among them. But, fundamentally, it’s also about declining interest in what the school board is up to, whether the city council will approve a new liquor license and other quotidian matters.

News organizations that hope to survive and thrive can’t settle for merely covering civic life — they have to teach their communities the importance of local news so that people will start paying attention and realize that what the mayor is doing is likely to have more of an effect on their families than anything that is taking place in Washington.

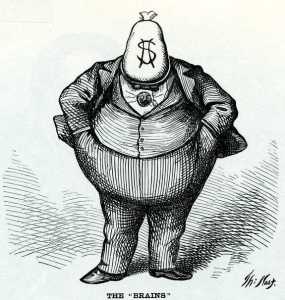

Such journalism is sometimes derisively called “eating your broccoli.” So kudos to the Sentinel for reimagining the intersection of journalism and audience engagement more along the lines of a cheeseburger and a beer. And look! Here comes the bride!

Correction: This article has been updated to correct the spelling of the town name of Marfa, Texas.

Talk about this post on Facebook.