One of my favorite newspaper rituals is reading the Declaration of Independence in the Boston Globe on the Fourth of July. Reading it on my iPad takes nothing away from the experience. Happy Independence Day!

Category: Culture

Talking about ‘Little People’ in Bridgewater on Oct. 3

If you’re in Southeastern Massachusetts, I hope you’ll consider dropping by the Bridgewater Public Library on Saturday, Oct. 3, at 11 a.m. I’ll be giving a talk on “Just Like Us: Images of Dwarfism from Tom Thumb to Reality TV,” based on my 2003 book “Little People.” The event is co-sponsored by Bridgewater State University.

You can read “Little People” online for free. But if you’d like to purchase a copy through the Harvard Book Store, just click here. I’ll also have a few copies available for sale after the talk.

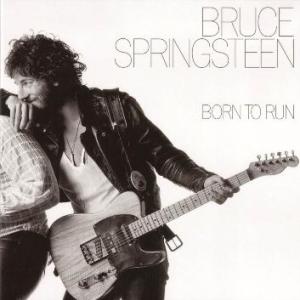

Forty years burning down the road

I don’t want to let the day end without taking note of the 40th anniversary of “Born to Run,” Bruce Springsteen’s third and best album.

I don’t want to let the day end without taking note of the 40th anniversary of “Born to Run,” Bruce Springsteen’s third and best album.

I was a 19-year-old Northeastern student in 1975, riding the bus from my hometown of Middleborough to Boston, where I was on co-op working in public relations at the United Way. I’d just about worn out my copy of “The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle,” his second album, and had seen an incredible show of his at the Music Hall in November 1974. I’d been bugging my local record store for months about “Born to Run,” and I bought it the day it finally came out.

And what an album it was. On one level, I was disappointed. I loved the ensemble playing and long jams on “The E Street Shuffle,” and I thought something had been lost with the single-minded focus on Springsteen that defines “Born to Run.” But more had been gained: a mythic quality that he hadn’t even hinted at previously. Some of it was a mirage. The Spectorish shimmer of “Backstreets” gets me every time, but the lyrics are a muddle. Still, it all works together, and “Thunder Road” may be the best song he ever wrote. (It’s also pretty devastating if you think of it as the prelude to “Racing in the Street,” from “Darkness on the Edge of Town.” From boisterous hope to resignation in three short years.)

Springsteen has maintained his integrity, and he’s still a great live performer. On Aug. 25, 1975, he was magic.

Barry Crimmins gets his overdue due in ‘Call Me Lucky’

What can you say about a film that stars someone you know and admire telling the world about being raped repeatedly — and nearly killed — when he was 3 years old?

Since we’re talking about Barry Crimmins, I would say that you should see it as soon as you can.

“Call Me Lucky,” directed by Bobcat Goldthwait, had its New England premiere on Saturday at the Somerville Theatre as part of the Independent Film Festival. As befits the subject, the documentary almost feels like two films. In the first part we meet Crimmins the caustic left-wing performer, who almost single-handedly created Boston’s comedy scene in the 1980s. In the second part, Crimmins comes to terms with his past as a survivor of childhood sexual abuse.

It was during this second phase that I got to know Barry. He revealed what had happened to him in the early 1990s in a harrowing front-page essay for The Boston Phoenix headlined “Baby Rape.” (I had a small role in copy-editing it, but most of the heavy lifting was handled by the late Caroline Knapp — and, of course, by Barry himself.) Later, Barry was a valuable resource as I was doing my own reporting about child sexual abuse. This was around the time Barry was engaged in a very public campaign against AOL and the pedophiles it allowed to run rampant in its chatrooms, a centerpiece of “Call Me Lucky.” Even though I can’t pretend to be a close friend of Barry’s, I’ve always been struck by his fundamental kindness and decency — a quality that comes through repeatedly in the film. (I was among many people Goldthwait interviewed, but I didn’t make the cut.)

Barry was a regular in the Phoenix, writing a satirical year-in-review piece every Christmas as well as other humor pieces. This 2003 takedown of Dennis Miller works as well today as it did 12 years ago. I still laugh when I recall his referring to George W. Bush as “the court-appointed president.” Barry was a big part of the Phoenix, and vice-versa. So I was pleased to see him pay tribute to the late managing editor Clif Garboden in the credits, saying he learned to write through Clif’s editing. Fittingly, Clif’s own classic apex as an angry humorist begins with a quote from Barry.

Despite its somber subject matter, there are plenty of laughs in “Call Me Lucky” — not just from Crimmins, but from many other comedians, including Jimmy Tingle, Margaret Cho and Lenny Clarke. The biggest laughs, though, are reserved for Ronald Reagan, who is seen attempting to explain what he knew and didn’t know about the Iran-Contra scandal. The man was a comic genius.

Barry was — and is — a comic genius as well. Because I wasn’t taking notes, I’ll rely on the press release for one of my favorite bits from the movie. A protégé of Barry’s, Bill Hicks, recalls that a member of the audience once yelled, “If you don’t love America why don’t you get out?” Crimmins’ response: “Because I don’t want to be a victim of its foreign policy!”

The story behind the Barry Crimmins documentary

Don Aucoin’s feature on the new Barry Crimmins documentary in today’s Boston Globe goes into harrowing detail about the sexual abuse Crimmins suffered at the hands of a babysitter and, years later, his battle with AOL, which he believed wasn’t doing enough to get child pornography off its site.

What Aucoin does not mention is that Crimmins first told his story in 1992 in a long, impassioned front-page essay for The Boston Phoenix. His piece was edited by Caroline Knapp, to whom Barry paid tribute when she died in 2002 at the age of 42:

She wisely, gently and calmly guided me through the most difficult piece of writing I have ever had to do. And then, long after her job was done, she followed up again and again to see how I was handling things after the piece was published.

The documentary, “Call Me Lucky,” directed by Crimmins’ friend and protégé Bobcat Goldthwait, is making its debut this week at the Sundance Film Festival. (Disclosure: I was among a large number of Crimmins’ Boston friends who was interviewed by Goldthwait last winter. I doubt very much that I made the cut.)

Barry is a caustic humorist who is also one of the most humane people I know. He was a big help to me when I was doing some of my own reporting on child sexual abuse. I’m looking forward to seeing “Call Me Lucky.”

Ethan Zuckerman on the limits of interconnectedness

The promise of the Internet was that it would break down social, cultural and national barriers, bringing people of diverse backgrounds together in ways that were never before possible. The reality is that online communities have reinforced those barriers.

That was the message of a talk Wednesday evening by Ethan Zuckerman, director of the MIT Center for Civic Media. Zuckerman, who spoke at Northeastern, is the author of the 2013 book “Rewire: Digital Cosmopolitans in the Age of Connection.” He is also the co-founder of Global Voices Online, a project begun at Harvard Law School’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society that tracks citizen media around the world.

I’ve seen Ethan talk on several occasions, and I always learn something new from him. Here is some live-tweeting I did on Wednesday.

https://twitter.com/dankennedy_nu/status/519966015254712320

https://twitter.com/dankennedy_nu/status/519968349418455040

https://twitter.com/dankennedy_nu/status/519969002249277440

https://twitter.com/dankennedy_nu/status/519970428459421696

https://twitter.com/dankennedy_nu/status/519970765496934401

https://twitter.com/dankennedy_nu/status/519972247323553793

https://twitter.com/dankennedy_nu/status/519973089506238464

https://twitter.com/dankennedy_nu/status/519974299156086784

One of the most interesting graphics Zuckerman showed was a map of San Francisco based on GPS-tracked cab drivers. Unlike a street map, which shows infrastructure, the taxi map showed flow — where people are actually traveling. Among other things, we could see that the African-American neighborhood of Hunters Point didn’t even appear on the flow map, suggesting that cab drivers do not travel in or out of that neighborhood (reinforcing the oft-stated complaint by African-Americans that cab drivers discriminate against them).

Since we can all be tracked via the GPS in our smartphones, flow maps such as the one Zuckerman demonstrated raise serious privacy implications as well.

https://twitter.com/dankennedy_nu/status/519974299156086784

https://twitter.com/dankennedy_nu/status/519975183260860416

We may actually be less cosmopolitan than we were 100 years ago.

https://twitter.com/dankennedy_nu/status/519977254718550016

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg likes to show a map suggesting that Facebook fosters interconnectedness around the world. In fact, upon closer examination the map mainly shows interconnectedness within a country. The United Arab Emirates demonstrates the highest level of international interconnectedness, but that’s because the UAE has an extraordinary number of guest workers who use the Internet to stay in touch with people back home. That leads Ethan Zuckerman to argue that maps often tell us what their designers want us to believe.

https://twitter.com/dankennedy_nu/status/519978709953294336

This final tweet seems out of context, but I’m including it because I like what Zuckerman said. It explains perfectly why I prefer Twitter to Facebook, even though I’m a heavy user of both. And it explains why many of us, including Zuckerman, rely on Twitter to bring us much of our news and information.

https://twitter.com/dankennedy_nu/status/519979810597400576

The economics of crowdfunded potato salad

I’m going to write a get-rich-quick book called “Finding Your Inner Potato Salad — And Making Your Financial Dreams Come True.” And, of course, I’ll fund it with a Kickstarter campaign. I’ll make that other Dan Kennedy look like an amateur.

Photo (cc) by Terry and published under a Creative Commons license. Some rights reserved.

Myth, reality and Jay Parini’s life of Jesus

On a long drive over the holidays, I listened to the podcast of “On Point” host Tom Ashbrook’s recent interview with the poet and author Jay Parini. The subject was Parini’s new book, “Jesus: The Human Face of God” (Icons).

On a long drive over the holidays, I listened to the podcast of “On Point” host Tom Ashbrook’s recent interview with the poet and author Jay Parini. The subject was Parini’s new book, “Jesus: The Human Face of God” (Icons).

I was fascinated. Here was someone who described himself as a believer — an Episcopalian, the denomination of my youth, no less — who spoke of Jesus and Christianity in terms of myth and metaphor rather than as some sort of rigid, literal reality. I wanted to see how he brought the seeming contradictions of belief and mythology together.

Unfortunately, the book itself does not quite live up to the promise of Parini’s conversation with Ashbrook, mainly because he tries to have it too many ways — starting with what it means to be a believer. “In its Greek and Latin roots,” he writes, “the word ‘believe’ simply means ‘giving one’s deepest self to’ something.” And he quotes St. Anselm: “For I do not seek to understand so that I may believe, but I believe so that I may understand.” To my way of thinking, that is putting the metaphorical cart before the metaphorical horse.

My principal unease with Parini, though, is that he writes about “remythologizing” Jesus without quite doing so. On the one hand, he suggests that the miracles Jesus performed and his resurrection are not meant to be taken literally. On the other, he does not rule out the possibility that they actually did happen. Parini doesn’t seem to think it matters all that much whether Jesus came back from the dead metaphorically or materially. Yet to me that’s the most important question.

I say that in full awareness of my own intellectual limitations. Like most people who were educated in a Western context, my thinking tends to be binary. My attitude toward religion is that it’s either literally true or it isn’t; and since it almost certainly isn’t, then it’s something I needn’t trouble myself with. Mind you, I have no patience for Christopher Hitchens-style atheism, and I’m intrigued enough by the whole notion of spirituality to attend a Unitarian Universalist church. But belief to me is a state of mind, based on provable facts, and not something I would give my “deepest self” to in the absence of such facts.

Still, there is much to recommend in Parini’s short biography. Parini is a warm and humane guide to the life of Jesus and the early roots of Christianity. He is especially valuable in explaining Jesus “the religious genius” who synthesized Jewish, Greek and Eastern ideas, especially in the Sermon on the Mount. Parini’s learned exploration of Jesus’ moral and spiritual teachings transcends the reality-versus-metaphor divide.

If you’re looking for answers, then “Jesus” is not for you. There are none, and Parini doesn’t pretend otherwise. But if you’re interested in a different way of thinking about Christianity, then Parini’s brief guide is a good place to start.

We have a pope

Well, of course it was marketing. That’s my response to the complaints that burst forth on Wednesday when we learned that Pope Francis had been chosen as Time magazine’s “Person of the Year” rather than NSA leaker Edward Snowden.

But I think Time made the right call journalistically, too. The Snowden revelations have had an enormous effect on the way we think about government secrecy. But Francis is a larger, more forward-looking choice. His early papacy has been fascinating, even if his pronouncements on matters such as abortion and homosexuality have been more about atmospherics than substance.

As a non-Catholic and non-Christian, I find myself wanting to know more about Francis — and where he intends to lead the world’s 1.2 billion Catholics. For all his progressive-sounding rhetoric (my favorite: “How can it be that it is not a news item when an elderly homeless person dies of exposure, but it is news when the stock market loses two points?”), it’s his recently announced initiative on the church’s child-rape crisis that will determine the fate of his papacy — and perhaps of the institution that he heads.

We hold these truths to be self-evident

One of my favorite Fourth of July traditions is reading the Declaration of Independence in The Boston Globe. It’s moved from print to the iPad, but the words ring just as clearly today as they did 237 years ago. (Believe it or not, the Declaration is behind the Globe’s paywall, but you can also read it here and in many other places.)

Every year I get something new out of it. I’m almost done with the audio version of Nathaniel Philbrick’s “Bunker Hill,” which — among many other things — documents the extent to which Boston’s Patriots put their faith in King George III while directing their wrath at his ministers.

Much changed between the Battle of Bunker Hill and the gathering in Philadelphia a year later. The Declaration includes a long bill of particulars against the king, preceded by this:

The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States.

My reading of Philbrick is that the political bonds between Britain and the Colonies had essentially been severed long before Samuel Adams began agitating — but the emotional bonds, as embodied by the king, took a lot longer to break.

Happy Fourth!