Photo 1909 by Lewis Hines

Previously published at WGBHNews.org.

From the Berkshires to the bayou, from the Pacific Northwest to southeastern Massachusetts, the COVID-19 pandemic is tearing through local newspapers.

Already under pressure from changes in technology and the decline of advertising, alternative weeklies and small dailies are teetering on the brink. Reporters have been laid off. Print editions have been suspended or cut back. Donations are being sought. And journalists everywhere are wondering if they have a future.

For the past 15 years or so, local, digital-only start-ups have stood out as a countervailing trend compared to the overall decline of the newspaper business. Though small in both number and scope, these entrepreneurial news organizations, both for-profit and nonprofit, have provided coverage that their communities would otherwise lack. Yet they, too, have been battered by the novel coronavirus.

“They’re stretching their journalistic capacity,” said Chris Krewson, executive director of the 200-member LION (Local Independent Online News) Publishers, at a virtual conference last week sponsored by Northeastern University’s School of Journalism, where I’m a faculty member. “Everyone’s seeing incredible jumps in traffic and audience and [newsletter] open rates and things like that. And the volume of stories has never been higher.

“At the same time,” he added, “the sorts of things that everyone has built their business around, certainly since 2010, are a challenge. You have a business built around where to go and what to do, and there’s nowhere to go and nothing to do. So you’re looking at the first waves of cancellations from advertisers.”

Over the weekend, I emailed a number of editors and publishers at free, digital-only news outlets to see how they were faring. Though they all said they are pushing ahead, they added that the economic and logistical challenges of covering the COVID-19 story have proved daunting. (Please click here for a complete transcript of our conversation.)

At least for the moment, the nonprofits have an advantage, since their funding — from grants, foundations and donations — tends to be in place months in advance.

“We operate on a tight budget, and are always scrambling for money for our long-term sustainability,” says Paul Bass, who runs the nonprofit New Haven Independent and WNHH Community Radio. “But we seek to set our budget each year at a level that can be supported by current deposits and a few multi-year commitments by our deepest-pocket long-term supporters, so that people know 12 months at a time that they have a job and the lights stay on.”

Dylan Smith, publisher of the nonprofit Tucson Sentinel in Arizona, worries about the long-term effect on his site — but adds that, for now, the reaction has been positive.

“We’ve been sent quite a number of three-figure donations out of the blue, and seen a substantial uptick in people signing up to contribute monthly,” he says. “That community support has really been heartening. Not only will it help keep the lights on, but the kind words and cold hard cash we’ve gotten let us know we’re doing something meaningful to help.”

By contrast, The Batavian, a for-profit site that serves Genesee County in western New York, is scrambling, according to publisher Howard Owens. “Two top-tier advertisers have dropped,” he says. “Our revenue is 95% advertising. I expect we’ll take a big hit before this is over.” He adds: “I’m more worried about my business’ ability to survive than I am worried about my own health. We have a PressPatron button on our site if anybody wishes to make a contribution.”

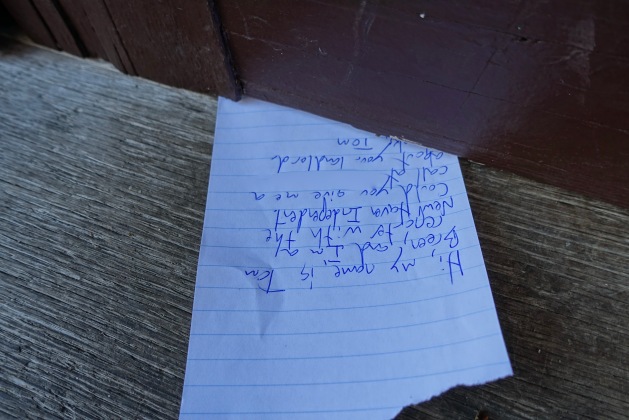

In at least one instance, the crisis has forced a publisher to postpone collecting any money at all. Jennifer Lord Paluzzi, a veteran journalist who recently launched her second start-up, Grafton Common, in the Worcester area, was hoping to ask for donations, but has decided to wait until the pandemic subsides.

“I was about to put a tip jar on my site that people could just put money in and help fund it,” she said at the Northeastern event. “But with everything that’s going on right now, with businesses closing, I’m like, OK, we’re going to skip the tip jar and entertain everybody.”

The need for social distancing may prove challenging to The Mendocino Voice, a for-profit site in California that is in the process of shifting to an employee- and member-owned co-op. The founders, publisher Kate Maxwell and managing editor Adrian Fernandez Baumann, had envisioned a series of meetings across Mendocino County to whip up enthusiasm and to refine the details of what the co-op would look like. But now they have to figure out other ways to do that.

“The challenge is how to work with the funders and re-create our plan for a series of community forums and member meetings virtually,” Maxwell says. “However, we cover a large area and are always looking for ways to better reach remote readers, so in the end this shift could be very valuable to refining the tools we use to engage with our readers and strengthen our membership campaign.”

Despite such difficulties, the journalists I reached all expressed enthusiasm for covering what may prove to be the biggest story of our lifetime.

“As an organization that focuses a lot of our effort on covering state and local government, it’s a massive story for us,” says Andrew Putz, editor of the Minneapolis-based nonprofit MinnPost. “I just looked, and we did 34 stories in the last week tied in some way to Minnesota’s response to the pandemic. So to answer your question more directly: We’re throwing everything we have at it.”

Adds Smith: “We’re working our asses off. I think I had 14 or 15 bylines in one day last week. And that’s not counting multiple updates to some stories.”

Although most of these small news organizations have offices, working at home is nothing new. Both Putz and Smith say they’ve been communicating with reporters via Slack. “We’ve been working remotely for a decade already,” says Smith. “I have a couple of reporters I haven’t even seen face-to-face yet in 2020.”

And all agree that health and safety come first. “If they feel like they must attend a meeting/press conference/interview,” says Putz of his reporters, “we’ve asked them to exercise their judgment — and to make sure they know that there’s no story that’s worth them jeopardizing their health.”

For the time being, Owens has abandoned his office in downtown Batavia. He says he and his wife, Billie Owens, the site’s editor, have an agreement that neither can leave the house without the other’s permission. Their one staff member as well as freelancers are all working from home.

“It’s not just about keeping them/us safe,” he says. “It’s about flattening the curve. We need to give our government, health-care systems and private sector time to build capacity to deal with a pandemic that will last for a year or two.”

The exception is Bass, who has not yet stopped his reporters (except for one in his 70s) from covering stories in person. He says his journalists have been instructed to stay six feet away from people they’re interviewing and photographing, and he will continue to reassess.

“My guess is, especially as government meetings shift online, we will be doing fewer in-person interviews,” Bass says. “Also, math suggests that some of us will get sick, which will certainly diminish our reporting capacity. But for now it’s full steam ahead, with fingers crossed. We love our community and feel we have an important role in strengthening it.”

Talk about this post on Facebook.

Eric Boehlert. Photo (cc) 2019 by kellywritershouse.

Eric Boehlert. Photo (cc) 2019 by kellywritershouse.

News organizations continue to grapple with the trolls under the bridge

By Dan Kennedy

On February 5, 2021

In Local News

Anika Gupta. Photo via LinkedIn.

Can comments on news platforms be salvaged? Hailed two decades ago as a forum for empowering what Dan Gillmor and Jay Rosen called “the former audience,” they have in all too many cases devolved into an open sewer of lies, hate and racism. Remember the adage that “our audience knows more than we do”? Well, there may be something to that. But it turns out that scrolling through the comments is not the way to tap into that wisdom.

The Philadelphia Inquirer this week became the latest news organization to drop most of its comments. Closer to home, when my other employer, GBH News, ended comments a few years ago in the course of upgrading its content-management system, I didn’t hear about a single complaint.

On Thursday, Anika Gupta, the author of “How to Handle a Crowd: The Art of Creating Healthy and Dynamic Online Communities” (2020), offered some common-sense ideas that were aimed not only at news sites but also at the larger challenge of how to keep virtual discussions from spinning out of control.

In a talk via Zoom sponsored by Northeastern University’s School of Journalism, Gupta discussed her study of Make America Dinner Again, started in 2016 by two women in the San Francisco Bay Area, Tria Chang and Justine Lee, to bring people with differing political perpectives together over food and conversation. It took off, and Facebook approached Chang and Lee with the idea of making it a Facebook group as well.

To the extent that it’s worked, Gupta said, it’s because the group has grown slowly (to date, there are still fewer than 1,000 members), with lots of personal intervention. Some of the steps they’ve taken include staying away from hot-button topics such as whether abortion should be legal or if teachers should have guns. Instead, they aim for “detailed, specific, ‘sideways’ questions,” as Gupta put it in her presentation. For instance, rather than asking about abortion rights, members were asked a lengthy question about how religious people justify a particular biblical quote.

They also implemented a “one-hour rule” that limits members to posting only one comment per thread per hour, which tends to keep the temperature down.

Some of the challenges they’ve faced, Gupta said, involve questions about what to do regarding members with false or offensive views. Their decision was to take aggressive action in such cases and encourage people to leave — a different approach compared to the one generally taken by the news business.

“A lot of news organizations are uncomfortable with this ‘if you don’t like it, you can leave’ attitude,” Gupta said.

I had a chance to ask Gupta about two issues that have bedeviled news organizations: Would requiring real names make a difference? And should comments be screened before they’re posted? Gupta’s take was that real names don’t matter all that much. Even in community online forums with real-names policies, she said, “you will be shocked about what people say about their neighbors.” (Actually, no, I wouldn’t.)

Moreover, insisting on real names can drive away people afraid of being harassed. That’s especially true with women, who, studies and anecdotal evidence show, are disproportionately singled out for online abuse.

Pre-screening, she added, is a problem because it is so labor-intensive, and it may not be realistic for larger media outlets. She also said pre-screening turns comments into something like letters to the editor, since commenters know their views are going to be read by someone at the news organization.

Although it can be difficult to find a news site that has healthy, productive comments, there are a few. One is the New Haven Independent, a nonprofit I wrote about in my 2013 book, “The Wired City.”

The Independent doesn’t require real names, but it does have a number of commenters who’ve used consistent pseudonyms over time, which Gupta said is helpful in maintaining civility. The site also screens every comment before it’s posted. The editor and founder, Paul Bass, believes that leads to more and higher-quality comments, since people who want to be constructive aren’t scared off.

Still, the Independent has had its glitches. As I wrote for the Nieman Journalism Lab a number of years ago, at one point an outbreak of sociopathy led Bass to shut down the comments temporarily. When they relaunched, commenters were required to register under their real names, though they could still post pseudonymously. That action put them on notice that they could be sued — Section 230, much discussed of late, protects the Independent, not the individuals who comment on the site.

Bass continues to see value in comments, writing in a public thread on Facebook this week:

Screening is essential. We screw up sometimes, and sometimes it gets toxic. But overall almost everyone involved with our site (readers, reporters, etc.) agrees that comments section is the best part. Lively, very wide range of points of view and racial/economic backgrounds; and some people who really know a lot more than we do! But occasionally it does feel like a sewer. I do feel comfortable zapping comments and banning people. Without our comments section, we would be more removed from readers, especially those who disagree with us. I learn so much from commenters!

I do wonder, though, if the Independent’s 2005 founding has something to do with Bass’ success with comments. Facebook was barely a thing at that time, and digital culture hadn’t become as toxic as it is today. By establishing expectations right from the start, Bass has been able to maintain a relatively civil environment for more than 15 years.

And I agree with Bass that screening — by humans — is essential. Anika Gupta said Thursday that screening by artificial intelligence isn’t going to be effective anytime soon, despite the efforts of Google to develop a system that would do just that.

At the local level, in particular, maintaining a useful comments platform is essential to keeping the audience engaged. Letting the trolls invade and taking action only after the damage has been done is exactly the wrong approach.

Become a member! For $5 a month, you can support Media Nation and receive a weekly newsletter with exclusive content. Just click here.