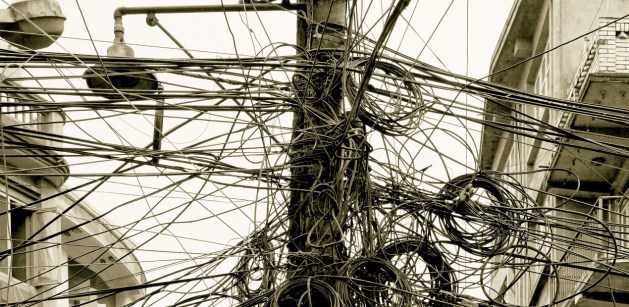

Photo via the Shorenstein Center.

Previously published at WGBHNews.org.

In just a few years, #fakenews has moved to the top of what we worry about when we worry about the news media.

Recently the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, based at Harvard’s Kennedy School, released a report seeking to document efforts to fight fake news, from Facebook, Google, and Twitter to academic institutions, from entrepreneurial start-ups to nonprofit foundations. The report, titled “The Fight Against Disinformation in the U.S.: A Landscape Analysis,” was written by Heidi Radford Legg, a journalist who is the director of special projects at Shorenstein, and Joe Kerwin, a Harvard senior.

“Trust in news has fallen dramatically and the rise in polarizing content, created to look like news, is being driven by both profiteers and malevolent players,” Radford Legg and Kerwin write. “Add to this a president that undercuts the credibility of the press on a daily basis and who has declared the press as an ‘enemy of the people.’ American journalism, already shouldering practically non-existent revenue models that have led to the decimation of quality local news, is in deep defense.” (Disclosure: My work is briefly cited in the report.)

What follows is a lightly edited email interview that I conducted with Radford Legg.

Dan Kennedy: You’ve provided a comprehensive overview of efforts to fight disinformation. What is the main takeaway? How do you hope your paper will be used?

Heidi Radford Legg: When I arrived at the Shorenstein Center, as a journalist trained to give context to a situation and who had long worked in upstart or for-profit media, I was fascinated by all the people in academia and in the foundation world who were stepping up to solve this existential crisis for our society. It became immediately clear to me that this was the story. Here was Craig Newmark, the founder of Craigslist, which essentially disrupted the newspaper classified revenue stream, giving $70 million to journalism and the fight against disinformation.

As an entrepreneurial journalist, having founded TheEditorial.com, I was all about disruption and innovation. However, we are now in this acute moment when a deluge of disinformation and misinformation plagues our information ecosystem — exponentially, thanks to this digital age. Local news revenue is being decimated, platforms are absorbing all of the attention economy dollars, and rogue players are penetrating our information pipeline. It is the perfect storm.

Thankfully, a few bold leaders have stepped in to try to put some guard rails in place while we wait for the platforms to self-regulate or be regulated. My hope is that this paper will inspire other funders and civic leaders to get involved, because the effects of disinformation and the breakdown of traditional journalism models are quickly eroding the ability to have an informed citizenry in our democracy.

Kennedy: You cite one of my heroes, Neil Postman, the author of “Amusing Ourselves to Death.”What do you think he would have to say about this media and cultural moment?

Radford Legg: I wonder if Postman might think he was too cheeky about the whole thing and should have warned us more desperately — the same way climate change advocates worry we are being too apathetic about the dire risks of climate change today. I will say, it is hard not to see that we are dumbing down as a society, with our attention span reduced to nanoseconds. I know some digital experts disagree with me and think we are at a point of great societal leaps with artificial intelligence. I am not there. I would take basic education on civics and critical thinking for all Americans, and an informed citizenry, at this point. Computer code is still binary. It is based on “this equals that.” While transformative and our future, I still believe in the ethical fortitude of the human when taught critical thinking and empathy.

Kennedy: Your section on how Facebook is fighting misinformation is appropriately skeptical, yet I sense that you accept the company’s assurances that it’s sincere about its efforts. I’m wondering if your views have changed since you finished writing this report given the never-ending stream of bad news coming out of the Zuckerborg. Siva Vaidhyanathan argues in his book “Antisocial Media” that Facebook can’t be fixed because it’s working the way it was designed to work. What do you think?

Radford Legg: I tried to stay unbiased in the reporting to list actual measures being taken by platforms at the time of the writing of this paper. I had two terrific Harvard student interns this summer, Joe Kerwin and Grace Greason, who spent hours tracking the media reports on measures the platforms were taking. We would compare the PR version to news articles by Wired, BuzzFeed, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Harvard’s Nieman Lab. You will remember that from April to August, there was a mad flurry of deplatforming of Facebook sites, scourging of Twitter accounts, and general clean-up by the social media giants — who likely knew they were being asked to testify in front of Congress in September. Our research leads up to the moment Twitter’s Jack Dorsey finally booted Alex Jones and Infowars off the site. We tried to stick to the facts.

I do think the platforms are taking steps, but what I would really like them to address is that they are now news organizations. Rather than media entertainment companies, they need to accept that they are owning the news, and it is time they begin to hire journalists and editors with a small percentage of the insane profits they reap in this new Attention Economy. This revenue, in the form of advertising fees, was what once funded local newsrooms, and that breakdown is part of the problem.

The Shorenstein Center’s Platform Accountability Project, IDLab, and Media Manipulation Case Studies Project are all working together to create a body of research and knowledge that will put pressure on the platforms and educate Congress on what is happening in the space. One way for people to join the effort is to fund our research at the Shorenstein Center. Our goal is to be at the intersection of media and politics and help inform legislation and policy around this urgent problem as we lead up to another Presidential election in 2020.

Kennedy: You describe an impressive set of initiatives by Google to help news organizations find their way toward financial sustainability and to keep disinformation out of its search results. Ultimately, though, I wonder if what Google really needs to do is work out a system of paying for the news content that it uses. I realize that’s probably outside the purview of your study, but do you have any thoughts on that?

Radford Legg: I write in the study that “one part of Google’s effort funds journalism while the other builds tools to sell back to them. Its approach is equal parts philanthropy and capitalism. Google’s tagline makes its intent clear: ‘To help journalism thrive in a digital age.’” The question remains, for whose benefit? Ours or their bottom line? I’m hoping for the former.

What I would really like to see is for the Google News Initiative, led by Richard Gingras, to fund a number of major research projects at leading media centers like ours around revenue models for local news. The Shorenstein Center’s Elizabeth Hansen has been studying membership models like the Texas Tribune and how small and medium-sized newsrooms compete in this global digital economy. Ethan Zuckerman at the MIT Media Lab is working on a project that could share ad revenue from major platforms with the journalists or outlets that wrote a particular story. Take Flint, Michigan. The journalists who broke that story should get the largest financial gain. Today, that is not the case. Google, Facebook, and any platform or major outlet profiting from the story with clicks, should help support that local journalism.

The platforms have all the access today. Facebook alone has 2 billion users and a cash balance of $41 billion and market cap of $407 billion. Google has a cash balance of $106 billion and a market cap of $731 billion. They should start to pay and hire vetted reporters and editors steeped in the tenets of journalism — to report facts and first-person accounts. One might say it is time they grow up and be the civic leaders in the room.

Kennedy: As you note, the Berkman Klein Center has documented asymmetric polarization, which shows that consumers of right-wing media are far more susceptible to disinformation than those whose sources are more mainstream or left-leaning. What can we do about this without arousing suspicions — and anger — that we are simply seeking to impose our own liberal and elitist views?

Radford Legg: Again I go back to local news. If people who are being radicalized on the web by polarized content were instead reading about the people who live next to them and consuming news about their own city’s innovation, challenges, and progress, I believe the country would be better off and less divided. Without a trusted and reliable source on the ground in their local communities, Americans are susceptible to dogma being sold by harvesters of the Attention Economy, who are polluting the information ecosystem with untruths and content intended to polarize and divide our nation.

We should work harder to be inclusive with those in other areas of the country. As reporters, the more we can cover those stories, the better for democracy. My dream is to find paths to having journalists funded in those towns who understand the people and culture, and who can bring local back into the national conversation. This will require funding, and that is where the platforms should step up.

Kennedy: We live at a time when the president himself is our leading source of disinformation, and he has managed to convince his most committed followers that he is the ultimate source of all truth. How difficult is it to fight against disinformation in such a climate?

Radford Legg: At the Shorenstein Center’s Theodore H. White Lecture, I sat at a table with a number of our Joan Shorenstein Fellows, of whom you were one. We debated this. Should we cover the president or should we ignore him and instead cover local news and stories of progress? Should we ensure that headlines don’t repeat lies? The table was divided. But at what point do we turn away from the media circus and return to the basics? What is going on in your city hall? What ideas are changing the way you live and work in your city, town, state? What can we as a nation learn from what is going on in Corning, New York, or Beaufort, North Carolina, Portland, Oregon or Maine, or McLean County, Kentucky? I am a local kid. I think that is where the lifeblood of a democracy lives.

Kennedy: Is there any hope?

Radford Legg: Always.

Today, given the dire state of revenue models for local news, we need the wealthiest and most influential to fund and promote the research and innovation experiments desperately needed today in local journalism, and we need everyone who believes in journalism to get involved, vote, and help bridge the polarization. The late Gerry Lenfest’s legacy gift in Philadelphia is a case study many of us are watching in local news. He put the fabled Philadelphia Inquirer and sister properties into a trust and endowed it with $20 million. That’s commitment to local and that is hope. Let’s hope it inspires more of the same.

Talk about this post on Facebook.