Saltmarshes behind J.T. Farnham’s in Essex, Sunday evening.

Month: July 2012 Page 2 of 3

This article was previously posted at the Nieman Journalism Lab.

Ownership matters.

It matters in New Orleans, where Advance Publications is cutting The Times-Picayune’s print edition from seven days a week to three — and gutting the staff —despite earning a profit and paying bonuses in 2010 and 2011.

It matters in Chicago, where Tribune Company — which may soon emerge from bankruptcy — got rid of its hyperlocal reporters at the Chicago Tribune and replaced them with Journatic, which outsources coverage, in some cases to the Philippines, and which until recently used fake bylines on some of its stories. (On Friday, the Tribune suspended its relationship with Journatic after a plagiarism complaint arose.)

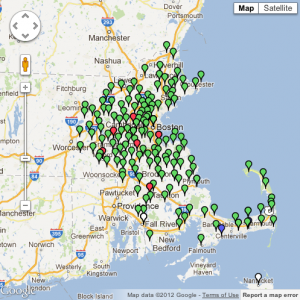

And it matters in the Boston area, where GateHouse Media — the national chain that owns more than 100 community newspapers here — is preparing to unveil a centralized in-house content farm whose work could eventually find its way into eastern Massachusetts.

Newspapers, the source of most local journalism, are weighed down by chain ownership and corporate debt. Independent online news sites are a promising alternative. But for-profit sites like The Batavian and Baristanet are too small to provide the full range of community journalism that was typical a generation or two ago. And larger nonprofits like the New Haven Independent and Voice of San Diego are rare, in part because the IRS has put a hold on new ventures.

So what can be done? Later this year, a community news site based on an entirely different ownership model is scheduled to debut in Haverhill, a blue-collar city of 60,000 about 45 minutes north of Boston on the New Hampshire line. The site, to be called Haverhill Matters, will be cooperatively owned, similar to a credit union or a food co-op. Neither for-profit nor nonprofit, the site, if it is to succeed, will depend on the goodwill and support of its members. And it is designed to be easily replicated in other cities and regions.

Haverhill Matters will be the first visible manifestation of the Banyan Project, an idea that veteran journalist Tom Stites has been working on for several years. I recently met Stites, whose long résumé includes editing stints at The New York Times and the Chicago Tribune, and Mike LaBonte, who chaired the site’s local organizing committee, at a restaurant in Haverhill to discuss their plans. (LaBonte stepped aside a short time later, citing health issues and the pressures of a new job.)

It was something of a reunion. I’d written for Stites several times when he was editor of the UU World, the Unitarian Universalist Association’s denominational magazine. I knew LaBonte through his volunteer work as an editor at NewsTrust, a social network that evaluates journalism for qualities such as fairness and sourcing; he’d led several workshops for my students.

What attracted Stites to the co-op model was his belief that newspaper executives, in their relentless pursuit of high-end advertising, had abandoned all but their most affluent readers. It’s a subject he has spoken and written about passionately, including at the 2006 Media Giraffe conference at UMass Amherst and in a series for the Lab last December.

Banyan sites such as Haverhill Matters are aimed at serving “news deserts,” a term Stites consciously adopted from “food deserts” — that is, lower-income urban neighborhoods where grocery stores are scarce and fast food restaurants proliferate. The idea is that a lack of fresh, relevant news can be as harmful to civic health as a lack of fresh, nutritious food can be to personal health.

That all sounds good, but where will the money come from? Stites said that Banyan sites would be supported through a combination of membership fees, grant money, and advertising. I told him that sounded exactly the same as the model used by nonprofit sites such as the New Haven Independent. Stites responded by emphasizing the benefits of membership in a co-op.

So let me draw a few comparisons between the Banyan model and the Independent. Stites hopes to sign up some 1,200 people who would pay $36 a year, bringing in a little more than $43,000 annually. The Independent asks for readers to pay $10 to $18 a month voluntarily; editor and founder Paul Bass told me he’s got about 100 voluntary subscribers paying a total of about $13,000 a year, which comes to less than 3 percent of his site’s $450,000 annual budget. Given that the Independent has been around for nearly seven years and serves a city twice the size of Haverhill, Stites’ goal is ambitious indeed. But there are differences in terms of the incentives.

Banyan sites such as Haverhill Matters would be free, as is the Independent. But in order to participate on the Haverhill site using community tools that Stites promises will be unusually sophisticated, readers will be asked to pay — a request that would become a requirement after several months. The Independent, by contrast, does not assess any mandatory charges. In keeping with the cooperative model, paid-up Banyan members will elect a board, which will in turn select the full-time editor. Readers will also be able to become members by contributing labor rather than time — perhaps by writing a neighborhood blog that appears on the site. If it works, in other words, a Banyan site would foster a sense of ownership and participation that other models lack.

“This is different from a hyperlocal news site,” Stites told me. “This is a community institution owned by a widely distributed, large number of community members. It has to be owned by members of the community, and they’ve got to support or it doesn’t happen.”

The next few months will be crucial ones. Currently, Stites is trying to raise money for the launch with a pitch at Spot.us. He and the organizing committee are planning a community meeting in Haverhill this September. And if all goes according to plan, Haverhill Matters will go live by the end of the year.

Stites is planning to launch Haverhill Matters with two paid staff members: a full-time, professional editor with roots in the city and a “general manager” whose job would be to build a community around the site and to write. Beyond that, his ideas for covering the news are evolving. Journalism students from nearby Northern Essex Community College would be involved. High school interns might be put to work assembling a community calendar. In our conversation, it came across as amorphous but potentially interesting — worth watching, but with compelling, useful journalism by no means assured.

Strictly speaking, Haverhill is not entirely a news desert, but it comes pretty close. The nearest daily, The Eagle-Tribune, is based in North Andover and owned by CNHI, a national chain based in Montgomery, Alabama. The paper publishes a daily Haverhill edition and a weekly, The Haverhill Gazette. But LaBonte told me that both were a far cry from the days when the Gazette was an independently owned daily paper.

“That was a thriving daily at one point,” LaBonte said. “What I’m hearing from an awful lot of new people is, how do I find out what is going on in Haverhill?”

By early 2013, one of the answers to that question might be a start-up website called Haverhill Matters.

The 15th Annual Muzzle Awards, published every Fourth of July (give or take) by the Phoenix newspapers of Boston, Providence and Portland, are now online and in print.

Inspired by my friend Harvey Silverglate, a prominent civil-liberties lawyer who wrote the sidebar on free speech in academia, the Muzzles highlight outrages against the First Amendment that took place in New England during the previous 12 months.

I’ll be talking about the Muzzles on Friday at 9 p.m. with Dan Rea on WBZ Radio (AM 1030). Hope you can tune in.

(This commentary is also online at the Huffington Post and at the New England First Amendment Center.)

Godwin’s law came to New Hampshire earlier this year. And Speaker of the House Bill O’Brien is retaliating against the Concord Monitor in a manner that may violate the First Amendment.

For those unfamiliar with the phrase, Godwin’s law — first espoused by Mike Godwin, a lawyer and veteran Internet free-speech activist — pertains to the tendency of online debate to devolve into Nazi analogies. As Godwin put it some years ago, “As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches 1.”

Maybe it’s the Internet effect, but the Nazification of real-world political debate has been under way for some time now. And so it was in mid-May, when state Rep. Steve Vaillancourt, a Republican, grew frustrated with what he saw as efforts by Speaker O’Brien, also a Republican, to silence him. So Vaillancourt directed a toxic remark at O’Brien: “Seig Heil.” He was ejected from the chamber and forced to apologize.

Enter Mike Marland, who draws editorial cartoons for the Concord Monitor. He depicted O’Brien with a Hitler-style mustache, holding a razor. The caption: “If the mustache fits …” You can see the cartoon here, along with a commentary by Monitor editor Felice Belman. Despite having written an editorial taking Vaillancourt to task for his Third Reich-style outburst, Belman defended Marland’s cartoon in defiance of Republican demands that the paper apologize:

When Marland submitted the O’Brien cartoon, there was significant discussion here among the senior editors and our publisher about whether to put it into the paper. In the end, we are not Marland’s censors. He is entitled to his view of the speaker, and his views are his own. This cartoon was harsh, no doubt. But it seemed on point, given last week’s circus. In fact, several Monitor letter writers have made a similar point — in words, if not images.

There matters stood until last Friday, when O’Brien held a news conference in his Statehouse office — and banned two Monitor reporters from attending. Concord Patch editor Tony Schinella, who was among those covering the event, wrote that the reporters, Annmarie Timmins and Matt Spolar, “were told they weren’t invited and were held at bay at the door.” Schinella also shot video of the reporters being turned away (above), and of O’Brien refusing to answer a question as to why he wouldn’t let them in. (Timmins’ own video of the encounter makes for must-see viewing as well.)

O’Brien’s spokeswoman later released a statement: “When the Concord Monitor proves they have chosen to become a responsible media outlet, we’ll be happy to invite them to future media events.”

As the Monitor put it in an editorial, “It’s hard to know which is more startling: a politician attempting to pick his own press corps or the notion that a politician — or a politician’s mouthpiece — gets to decide what constitutes ‘a responsible media outlet.’ Are these people new to this country?”

Now, depending on your point of view, you might think O’Brien’s behavior was either boorish or principled. But perhaps you wouldn’t question his right to do it. Indeed, even the Monitor editorial included this: “There’s nothing requiring O’Brien to let the Monitor into his press conference.”

In fact, though, O’Brien may well have been interfering with the Monitor’s First Amendment right to cover the news.

Several decades ago, a similar situation unfolded in Hawaii, where an aggressive reporter for the Honolulu Star-Bulletin named Richard Borreca butted heads with the mayor, Frank Fasi. Fasi decided to ban Borreca from regularly scheduled news conferences at his City Hall office. The Star-Bulletin went to court. And in the 1974 case of Borreca v. Fasi, U.S. District Court Judge Samuel King ruled that Fasi had to open his news conferences to all reporters. King wrote:

A free press is not necessarily an angelic press. Newspapers take sides, especially in political contests. Newspaper reporters are not always accurate and objective. They are subject to criticism, and the right of a governmental official to criticize is within First Amendment guarantees.

But when criticism transforms into an attempt to use the powers of governmental office to intimidate or to discipline the press or one of its members because of what appears in print, a compelling governmental interest that cannot be served by less restrictive means must be shown for such use to meet Constitutional standards. No compelling governmental interest has been shown or even claimed here.

Judge King made it clear that no member of the press was entitled to special privileges. If the mayor wanted to grant interviews to some reporters but not others, that was his prerogative. If he refused to answer a reporter’s questions, that was within his rights as well. But he could not discriminate against some members of the press when scheduling a formal, official event such as a news conference.

The parallel between the Honolulu and Concord situations is pretty obvious, though it’s impossible to say whether a different court would come to the same conclusion nearly 40 years later. In a commentary published by the Monitor, Steven Gordon, a lawyer, argued that O’Brien’s action may well have been an unconstitutional abridgement of the paper’s free-press rights.

I just hope Speaker O’Brien comes to his senses and realizes that the Monitor was well within its rights to run the Hitler cartoon no matter how much he may wish it hadn’t done so. He, on the other hand, has no right to discriminate against a media outlet he doesn’t like.

From the New York Times: “Mickey Mouse and Minnie Mouse appeared on a television broadcast with North Korea’s new leader, Kim Jong-un. The reason was not clear.”

GateHouse publications and websites in Massachusetts. Click on map for interactive version at gatehousemedia.com.

The Journatic story keeps spreading. Today David Folkenflik summarizes what we know so far for NPR’s “Morning Edition,” bringing the tale of outsourced local news and fake bylines to many millions more listeners than those who first heard about it on “This American Life.” And Folkenflik has more on GateHouse Media’s decision to replace Journatic with a similar in-house operation — minus the fake bylines, which Journatic itself has said it will stop using.

There have been a few other developments as well. Among the more interesting is a post written by Mathew Ingram for GigaOm, who took issue with critics of Journatic by arguing that the real problem was a resistance to new ways of doing things. Ingram writes (the links are his):

Critics of the Journatic model, including Mandy Jenkins of Digital First Media and Anna Tarkov at the Poynter Institute, seem to want newspapers to continue to produce hyper-local community journalism in the traditional way, with reporters based in the community writing traditional stories. But given the kinds of financial pressures on the newspaper industry, that may simply not be viable for outlets like the [Chicago] Tribune or GateHouse. That’s not to say they shouldn’t devote resources to those communities, but it does mean that looking at alternative models for some kinds of content makes sense as well.

When Tarkov and I debated the issue with Ingram on Twitter yesterday, his first response was, “If I am defending anything, @dankennedy_nu, it’s the idea of experimenting with new ways of doing journalism. Is that bad?”

The problem is that there’s new and there’s new. The low-cost nonprofit, online-only model being tried in places like New Haven and San Diego, rebuilding local journalism through neighborhood reporting and civic engagement, is new. Hiring people in the Philippines to write news briefs for your local paper under Anglo-sounding bylines — well, that’s new, too. Not everything new should be embraced.

Also on Thursday, Tarkov had a follow-up that included a memo to the Journatic troops from chief executive Brian Timpone.

And speaking of memos, I received from a trusted source a memo from David Arkin, vice president of content and audience for GateHouse Media, explaining GateHouse’s decision to stop using Journatic and to replace it with something similar in-house. GateHouse owns more than 100 community newspapers in Eastern Massachusetts, though none had any Journatic content imposed on them. The full text of the memo follows:

All,

You may have read recently in industry trade publications that GateHouse Media has ended its relationship with content-producer Journatic.

Journatic creates local content like news briefs, calendar items and submitted education content such as honor rolls for newspapers. We started working with Journatic more than a year ago and had been using the service at nearly 30 GateHouse newspapers.

Since we didn’t use the service at all of our papers, we never communicated our partnership with this vendor to the company.

As you likely have read on Poynter and other blogs this week, we have decided to end the relationship with Journatic and build a similar service with central corporate staff for the newspapers that were using the Journatic service. We are in the process of ramping up a 10-person team that will produce this content for the newspapers.

We decided to end the relationship with Journatic for a few reasons:

— Journatic had trouble providing the kinds of content that our newspapers really needed. They provided a lot of content but weren’t successful in choosing the right kind of calendar items and news briefs.

— We spent too much time centrally and locally addressing errors with their content.

— We discovered we could produce process-oriented content that our newspapers really wanted at a more economical price than Journatic.

We have been working on this move for several months. The news this week that Journatic put fake bylines on stories reaffirmed our decision to leave, but a decision to end the relationship had been made months beforehand.

Bringing the service in-house has helped target the kind of content newspapers really want, and we’re making good progress toward cleaner copy. Producing that content centrally takes great coordination and communication, something we can manage better than a vendor.

We support Journatic’s model, which is to take process-oriented content out of newsrooms to allow our newspapers to focus on high-quality original reporting. We believe handling that community content centrally will put us in a better position to achieve a higher level of enterprise reporting at our newspapers.

Our goal is to transition all newspapers currently using Journatic to our centralized group by August and to ensure the service we’re providing is excellent. After that we’ll evaluate whether the service could be implemented at more GateHouse newspapers.

If you have any questions, don’t hesitate to contact me.

Thanks,

DADavid P. Arkin

Vice President of Content & Audience / GateHouse Media, Inc.

My source, a GateHouse insider, analyzes Arkin’s memo thusly: “From my perspective, there is a very narrow subset of stuff that could be assigned to a Journatic-type operation that could potentially free up my time for more worthy pursuits. The key to Arkin’s statement, of course, is the degree to which the intent of contracting with a service like Journatic or building a similar operation in-house is to free us up for more enterprise reporting, multimedia, social media, etc., rather than just to ‘decrease the surplus population.’ Time will tell, I suppose.”

If you care about local news, then you must listen to a report on “This American Life,” broadcast last weekend, that exposes a scandal whose importance can’t be overstated.

If you care about local news, then you must listen to a report on “This American Life,” broadcast last weekend, that exposes a scandal whose importance can’t be overstated.

The story is about a company called Journatic, which produces local content for newspapers using grossly underpaid, out-of-town reporters — including cheap Filipino workers who write articles under fake bylines.

And how great is it that “This American Life,” damaged earlier this year when it was victimized by fake journalism, has now exposed fake journalism elsewhere? Here is the Chicago Tribune — a major Journatic client — lecturing “TAL” on journalism ethics earlier this year.

After you listen, be sure to read the detailed back story, written by Anna Tarkov for Poynter.org.

Unfortunately, the broadcast aired just a few days before the Fourth of July, at a time when few people were paying much attention to the news. I hope it has the impact that it should.

The star of the “TAL” segment is a journalist named Ryan Smith, who kicks things off with a killer anecdote. Smith tells producer Sarah Koenig that he drew an assignment to write a story about a “student of the week” for the Houston Chronicle. He called the principal, who suggested he swing by the school the next day.

Smith told him he’d rather do it by phone, but he didn’t tell him the reason: he was actually some 1,000 miles away.

Both Koenig and Tarkov interviewed Journatic chief executive Brian Timpone, who apologized for nothing and spewed forth a torrent of rationalizations and excuses: the fake bylines were to protect employees from lawyers; the Filipinos don’t actually write stories (they do); there’s no value to having reporters live in the community for routine local coverage such as police-blotter news and budget updates; and Journatic is providing coverage to communities that would otherwise have none.

Well, none might be preferable to the “‘pink slime’ journalism” (Smith’s felicitous description) that Journatic produces. Moreover, if the Chicago Tribune uses Journatic stories in its hyperlocal coverage in order to suck advertising money out of pizza shops, funeral homes and other businesses, it becomes that much harder for would-be entrepreneurs to start their own local news sites.

Since the “TAL” story broke, we’ve been learning more about who’s using Journatic material. The Tribune, the Houston Chronicle, the San Francisco Chronicle and the Chicago Sun-Times have all made use of Journatic, and are now in various degrees of renouncing it.

Of more local interest: so has GateHouse Media, a national chain that owns more than 100 papers in Eastern Massachusetts — mostly weeklies, but also some dailies, including the Patriot Ledger of Quincy, the Enterprise of Brockton and the MetroWest Daily News.

According to a follow-up story by Tarkov, Journatic copy never made it into GateHouse’s Massachusetts properties. But the debt-ridden corporation is now setting up its own Journatic-like operations in Boston and in Rockford, Ill. Who knows where those honor rolls, obituaries and police logs will be coming from? (The blog post I’ve linked to suggests the centralized operations will be limited to design and layout. Tarkov’s story, though, references 10 “content providers” who will be based in Rockford.)

The media-reform group Free Press has mobilized over the Journatic revelations, with Libby Reinish summarizing the findings and Josh Stearns offering some advice on how to tell if what you’re reading is the real thing. Inevitably, Free Press has started a petition drive as well.

Unfortunately, the forces that make something like Journatic possible are very real. It’s expensive and labor-intensive to do local journalism right, and the crisis that has befallen the newspaper industry in recent years has made it that much harder. But this is truly beyond the pale. Even Patch, with its top-down, cookie-cutter approach, has journalists in each of its communities.

Ultimately, though, the solution will come from the bottom up, community by community, as is already the case with enterprises such as the New Haven Independent, the Batavian and dozens of others. Have a look at Authentically Local, an umbrella group of independent local sites organized by Debbie Galant, the co-founder of Baristanet in northern New Jersey.

Another potentially interesting experiment in local journalism will get under way later this year. The Banyan Project, begun by veteran journalist Tom Stites, will launch a test site in Haverhill to be called Haverhill Matters. The secret sauce is cooperative ownership, similar to a credit union or a food co-op. You’ll be reading more about Banyan at Media Nation in the weeks and months to come.

At one point in the “TAL” broadcast, Koenig says to Smith, “You are so fired.” It is perhaps a sign of how little the Journatic folks care about their reputation that, in fact, he hasn’t been. In an email to Jim Romenesko, Smith says it’s been business as usual, and that he’s received new assignments from his editor, who recently relocated from St. Louis to Brazil.

“I’m going to work the rest of the week,” Smith wrote, “and then resign.”

When bad reviews lead to worse comments

By Dan Kennedy

On July 19, 2012

In Media

Negative reviews leading to death threats and rape threats? That’s what they’re claiming at the film site Rotten Tomatoes, where comments to reviews of the new Batman movie, “The Dark Knight Rises,” have been turned off, according to the Los Angeles Times.

The hateful rants show how difficult it can be to keep online conversations on track. I’m not a movie buff, and I rarely visit Rotten Tomatoes, so I don’t have an opinion regarding the way comments are monitored there. But editor-in-chief Matt Atchity told the Times that he had seven people moderating “Dark Knight” comments before he finally pulled the plug. Click here for Atchity’s message to readers.

Atchity also said his next step may be to integrate the commenting system with Facebook, which is probably a good idea. A lot of news sites have found that Facebook comments tend to be more civil, which no doubt is related to the mindset people are in — they’re checking in with their friends, they’re sharing pictures of their cats. And, of course, they are usually using their real names, complete with pictures of themselves.

Earlier this year, the New Haven Independent, a nonprofit news site widely admired for the way it uses comments to enhance its coverage, ran into a crisis that led it to shut down commenting for two weeks. When it reopened, it was with new, stricter policies. (See this and this.)

Engaging in a conversation with your users is necessary and useful. If they don’t feel like they’re part of your site, they’ll go somewhere else. But doing it right is not easy.