Donald Trump and Nancy Pelosi in happier times. 2017 photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Previously published at WGBHNews.org.

Was President Trump’s bipartisan outreach in his State of the Union address Tuesday night a cynical attempt to recast himself as something he fundamentally is not? Or was it an even more cynical attempt to be seen as bipartisan while winking and nodding to his hardcore supporters? As Lily Tomlin once observed, “No matter how cynical I get, I can’t keep up.” I thought it was clear that Trump was pursuing the latter course. So take this as my attempt to stay ahead of the Tomlin curve.

The conventional take was expressed in The Wall Street Journal by Gerald Seib, who wrote: “When Donald Trump became president, there was reason to believe he might govern as he campaigned, almost as an independent, standing apart from both parties, perhaps even with an ability to bridge the two parties because he was beholden to neither of them. And for the first half an hour of his State of the Union address Tuesday night, that was the very tone he set in his remarks in the House chamber. He opened his arms to Democrats, declaring that Americans are ‘hoping we will govern not as two parties but as one nation.’”

But is that really what Trump did? Consider:

- Near the beginning of his speech, the president said that “the agenda I will lay out this evening is not a Republican agenda or a Democrat agenda.” Referring to the Democratic Party as “the Democrat Party” is a slight that goes back decades, as then-NPR ombudsman Alicia Shepherd explained in 2010. It was a calculated way for Trump to signal to his base that he was reaching out to Democrats while actually doing the opposite.

- Trump refused House Speaker Nancy Pelosi the courtesy of introducing him, as is the longstanding custom at the State of the Union. Kate Feldman noted the snub in New York’s Daily News, although she also observed that “he and Pelosi did share a cordial handshake during the first standing ovation.”

- Much later in his 82-minute stemwinder, Trump began ranting about the evils of socialism — “as if it had gotten particularly far along,” snarked Jim Newell in Slate. Trump’s remarks were apparently aimed at Congress’ two high-profile democratic socialists, Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and they seemed to have little effect. The #NeverTrump conservative Max Boot bemusedly pointed out in The Washington Post that Trump “equated [socialism] with Venezuela rather than, say, Denmark.” But it was a sign that Trump is prepared to go full Red Scare in what will surely be a desperate attempt to win re-election.

“Trump and his advisers can see he’s in a corner,” wrote the liberal commentator Josh Marshall at Talking Points Memo. “He needs to try to get some footing with a less confrontational, more unifying posture that most Presidents at least optically try to govern from.”

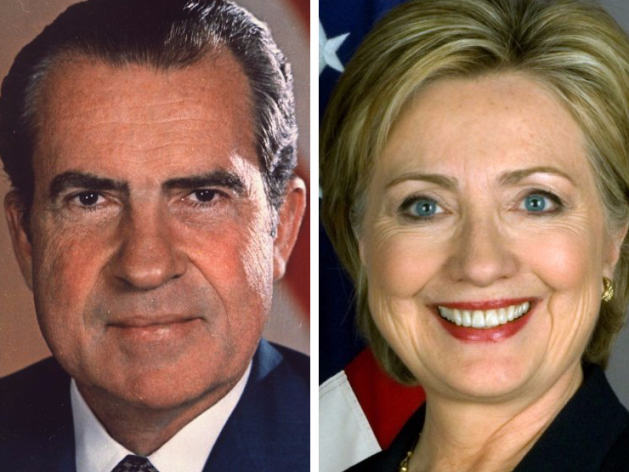

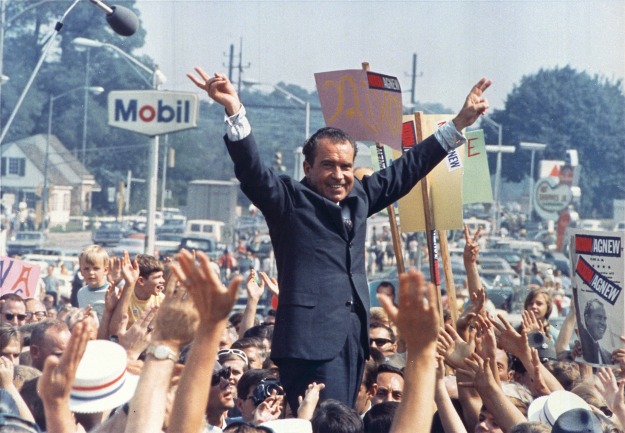

Other than Trump’s phony bipartisanship, his customary fear-mongering about undocumented immigration and crime, and his introduction of some truly admirable guests (every one of whom exuded a decency that was entirely absent from the podium), what struck me most was an unforced error in which he directly drew a parallel between himself and Richard Nixon.

“An economic miracle is taking place in the United States — and the only thing that can stop it are foolish wars, politics or ridiculous partisan investigations,” Trump said, a direct reference to the ongoing investigations into his campaign, his businesses, and his presidency. “If there is going to be peace and legislation, there cannot be war and investigation. It just doesn’t work that way!”

As Philip Bump pointed out in The Washington Post, Nixon said something remarkably similar in his 1974 State of the Union speech: “I believe the time has come to bring that investigation and the other investigations of this matter to an end. One year of Watergate is enough.” Bump’s riposte: “It wasn’t quite enough, as it turned out.”

The Democrats’ official response to Trump’s speech, delivered by Georgia Democrat Stacey Abrams, was unusually effective as these grim rituals go. Abrams gave an upbeat, warm talk while simultaneously scorching Trump over the recent government shutdown (she said she helped serve meals to out-of-work federal employees) and talking frankly about voter suppression. Abrams lost a close race for governor last November amid accusations that a variety of Election Day problems had resulted in thousands of voters in Democratic areas being turned away.

Who was watching Tuesday night? Mainly Trump voters. According to CNN polling director Jennifer Agiesta, people who viewed the speech “were roughly 17 points more likely than the general public to identify as Republicans.” And they liked what they saw, with about 60 percent giving it a thumbs-up.

Trump’s approach was pretty standard for him: Appeal to his shrinking but loyal base in the hopes that he can parlay their enthusiasm into another Electoral College victory. We are a very long way from knowing whether it will work — or even if he’ll be on the 2020 ballot given the various investigations swirling around him. It didn’t work out for Nixon. The final chapter of the Trump presidency has yet to be written.